Paul had tried to say it a hundred different ways. On Beatles for Sale, he’d tried laying out his case to Jane Asher logically:

Hey, what you’re doing, I’m feeling blue and lonely!

Would it be too much to ask you

What you’re doing to me?

You got me running, and there’s no fun in it!

Why should it be so much to ask of you

What you’re doing to me?

On Rubber Soul, he’d tried exhorting her:

I’m looking through you! Where did you go?

I thought I knew you! What did I know?

You don’t look different, but you have changed!

I’m looking through you; you’re not the same!

On his double-sided single (with “Day Tripper”), he’d tried warning her:

Try to see it my way,

Do I have to keep on talking ’til I can’t go on?

While you see it your way,

Run the risk of knowing that our love may soon be gone!

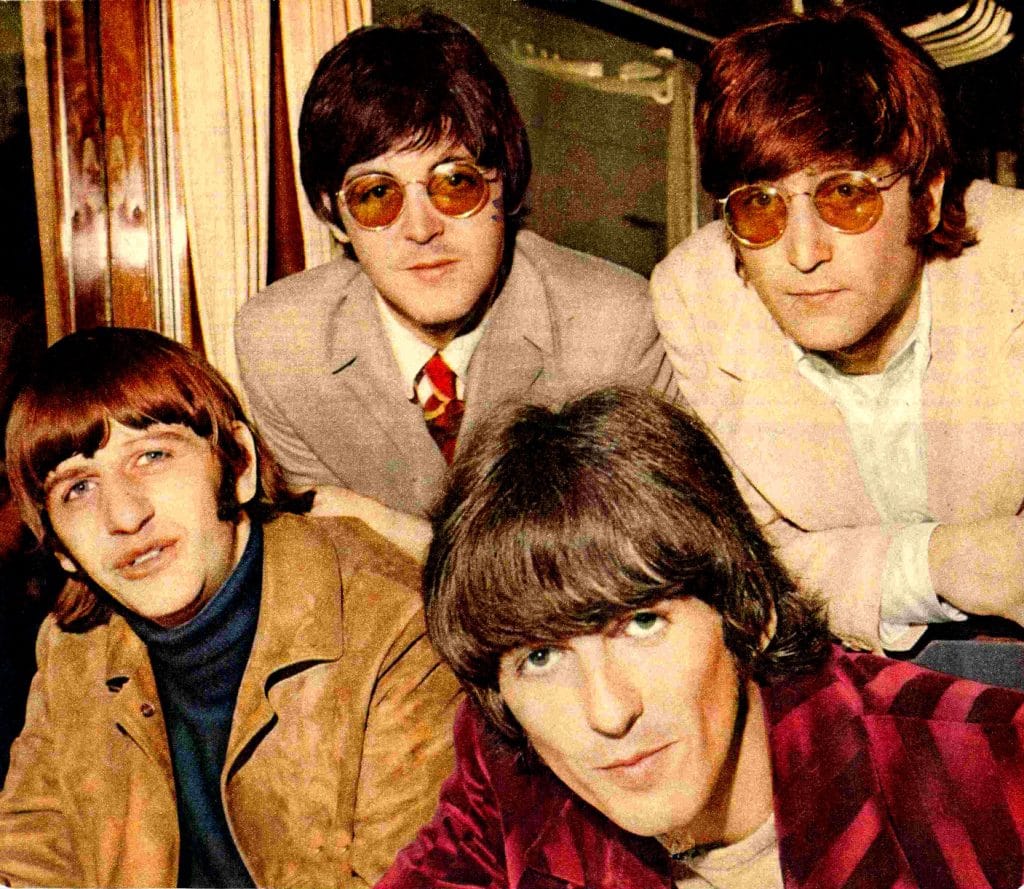

For years, in song after song after song, only the melody had changed. But the lyrics had been pretty much the same: “I need you here. I need you to give up what you’re doing and be with me. If you can’t find a way to be with me, we’re eventually going to come to an unhappy end.” That was the general thesis statement in “You Won’t See Me.” It was intrinsically implied in “All My Loving.” Paul’s basic theme was always there.

But Paul’s words had done no good. Jane had continued to pursue her glamorous career as a successful actress. She had continued to travel the globe and forge her own way in the world, and Paul was at the end of his rope, really.

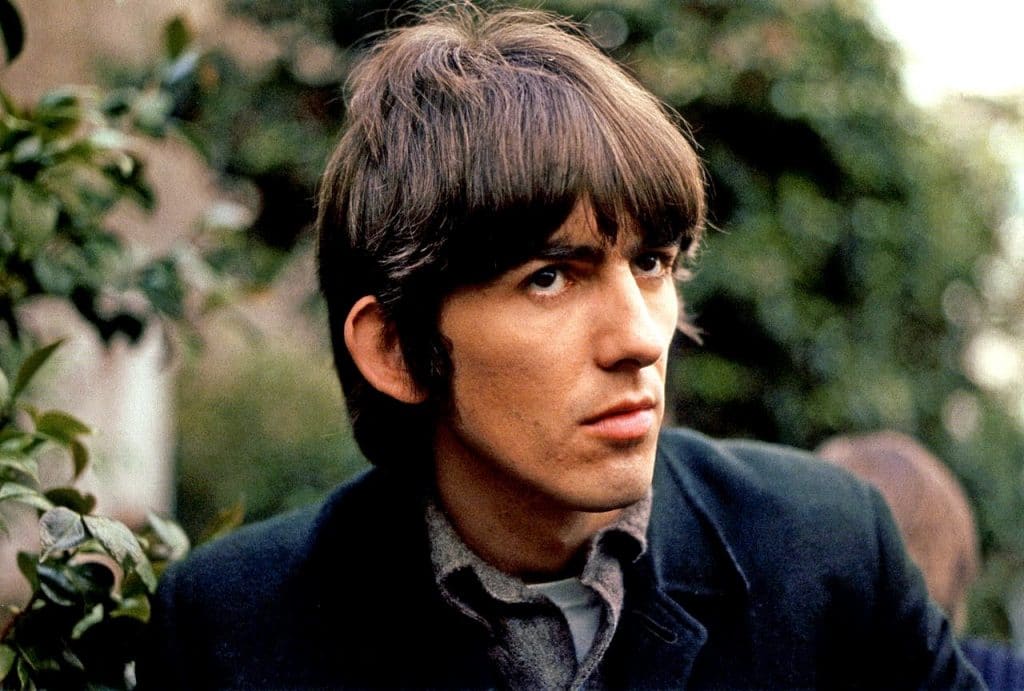

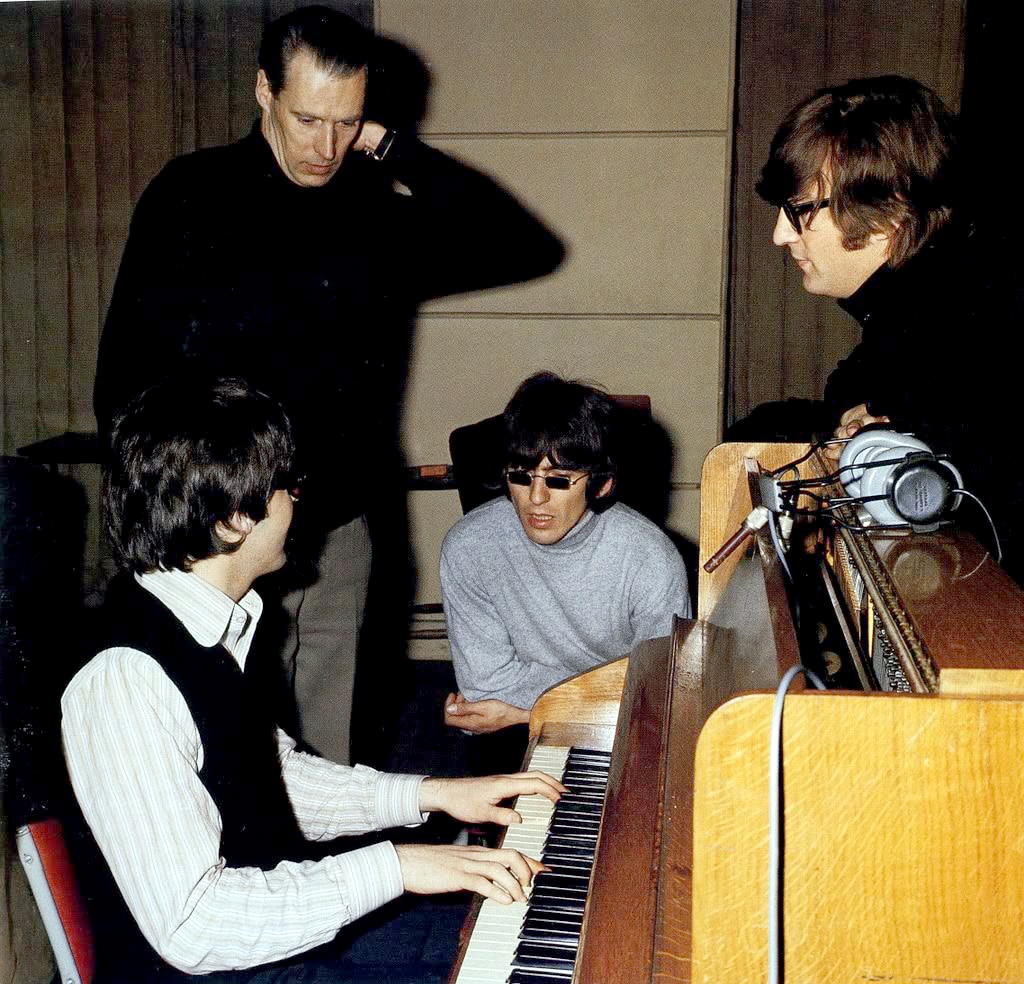

So, on Revolver, he sat down to write to her one last time, to woo her, to create a love song that would haunt her and say in the most enchanting way he knew how: “This is what our life could be, if you would simply be with me. Here’s the nirvana. Here’s the perfect world we could have, if only…”

And for Paul, whose wheelhouse was generally his incredible music – not his lyrics – this song is special. It’s poetry. It’s lovely, sincere poetry, written with a master’s hand. I know you’ve heard it a million times. You know it by heart. But you know the song. Take time now to read the poetry aloud. Forget the heartbreaking melody. Just speak (or whisper) the words to yourself. Try it.

This is Paul’s plea. And it’s poignant. It’s a vision for “the maiden faire” who has always eluded him. It’s one last chance…

To lead a better life

I need my love to be here!

Here, making each day of the year…

Changing my life with a wave of her hand!

Nobody can deny that there’s something there.

There, running my hands through her hair…

Both of us thinking how good it can be…

Someone is speaking, but she doesn’t know he’s there.

I want her everywhere

And if she’s beside me I know I need never care…

But to love her is to need her everywhere, knowing that love is to share!

Each one believing that love never dies,

Watching her eyes…and hoping I’m always there…

I want her everywhere

And if she’s beside me I know I need never care!!!

But to love her is to need her everywhere, knowing that love is to share…

Each one believing that love never dies

Watching their eyes and hoping I’m always there

I will be there, and everywhere

Here, there and everywhere.

And with that, Paul McCartney’s case is closed. Because really, could it be more plain, simple, honest, or touching?

One last time, Paul has laid out his evidence and vision to the girl he can’t quite pin down. (“I need you everywhere, knowing that love it to share.”) He has asked her one final time to relinquish the things that pull her away from him and to make him her world. And he has done it so effectively that he realizes if she declines, this time the offer must expire. This time, he will understand. This time, he will move on.

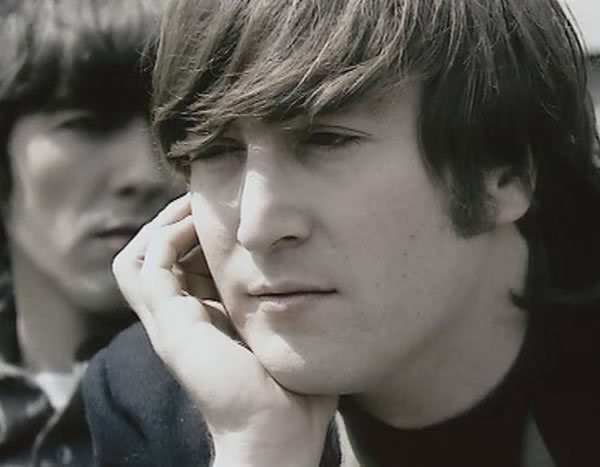

When asked about this song, John Lennon said that if he were on a desert island and could only have a limited number of tunes to cherish for the rest of his life, this would be one of his picks. This song. Because for a lyricist like John, this lonely, despairing plea speaks volumes.

“Here, There, and Everywhere” is truly one of Paul McCartney’s best because it comes from the heart. It’s not a white-washed, thumbs-up, “silly love song.” It’s a dramatic final gesture. Sadly, however (or maybe not!), this proposal was not enough. And when Jane Asher turned and moved in another direction, that paved the way for the entry of Linda Eastman.

Yes, here, there, and everywhere, Paul’s story has a happy ending. Always. Even if it was not the one anticipated.

Jude Southerland Kessler is the author of the John Lennon Series: www.johnlennonseries.com

Jude is represented by 910 Public Relations — @910PubRel on Twitter and 910 Public Relations on Facebook.