Side One, Track Four

“Love You To:” Now For Something Completely Different

by Jude Southerland Kessler and Susan Shumsky

Through 2023, the Fest for Beatles Fans blog has been moving track-by-track through The Beatles’ incredible 1966 LP, Revolver. This month, author Susan Shumsky, D.D., who has 20 books in print in English, 39 foreign editions, and 49 book awards, and has recently released The Inner Light: How India Influenced The Beatles, will provide our “Fresh New Look” at this pivotal George Harrison song.

Shumsky studied and lived in the ashrams of The Beatles’ mentor Maharishi Mahesh Yogi for two decades, spending six of those years on his personal staff. A spiritual teacher and producer of holistic conferences at sea, spiritual retreats, and tours to sacred destinations, she has done over 700 speaking engagements and 1300 media appearances, including Cosmopolitan magazine, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Fox News TV, and William Shatner’s “Weird or What?” In addition, she has appeared in several films, including the Beatles documentaries “The Beatles and India” and “Here There and Everywhere.” Susan has been an essential part of our Fest Family for years, speaking at both the New Jersey and Chicago Fests.

For our June study, Susan joins Fest blogger Jude Southerland Kessler, author of the five-volume John Lennon Series – and the new audiobook of She Loves You (Vol. 3 in the series) – for this in-depth look at “Love You To.”

What’s Standard:

Date Recorded: 11 April 1966

Time Recorded: 2:30 p.m. – 7:00 p.m. (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 72)

Studio: EMI Studios, Studio 3

Tech Team

Producer: George Martin

Balance Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil McDonald

In That Magic Feeling, John C. Winn tells us that on 11 April 1966, this was recorded:

A1 – George recorded the basic rhythm track by singing and accompanying himself on acoustic guitar (identified by Margotin and Guesdon as his Gibson JE-160). Paul provided backing vocals on the last word of each verse.

A2 – Paul played fuzz bass, using a volume pedal to “swell the notes.”

A3 – Then, the sitar, tambura, and tabla are overdubbed. Anil Bhagwat plays the tabla.

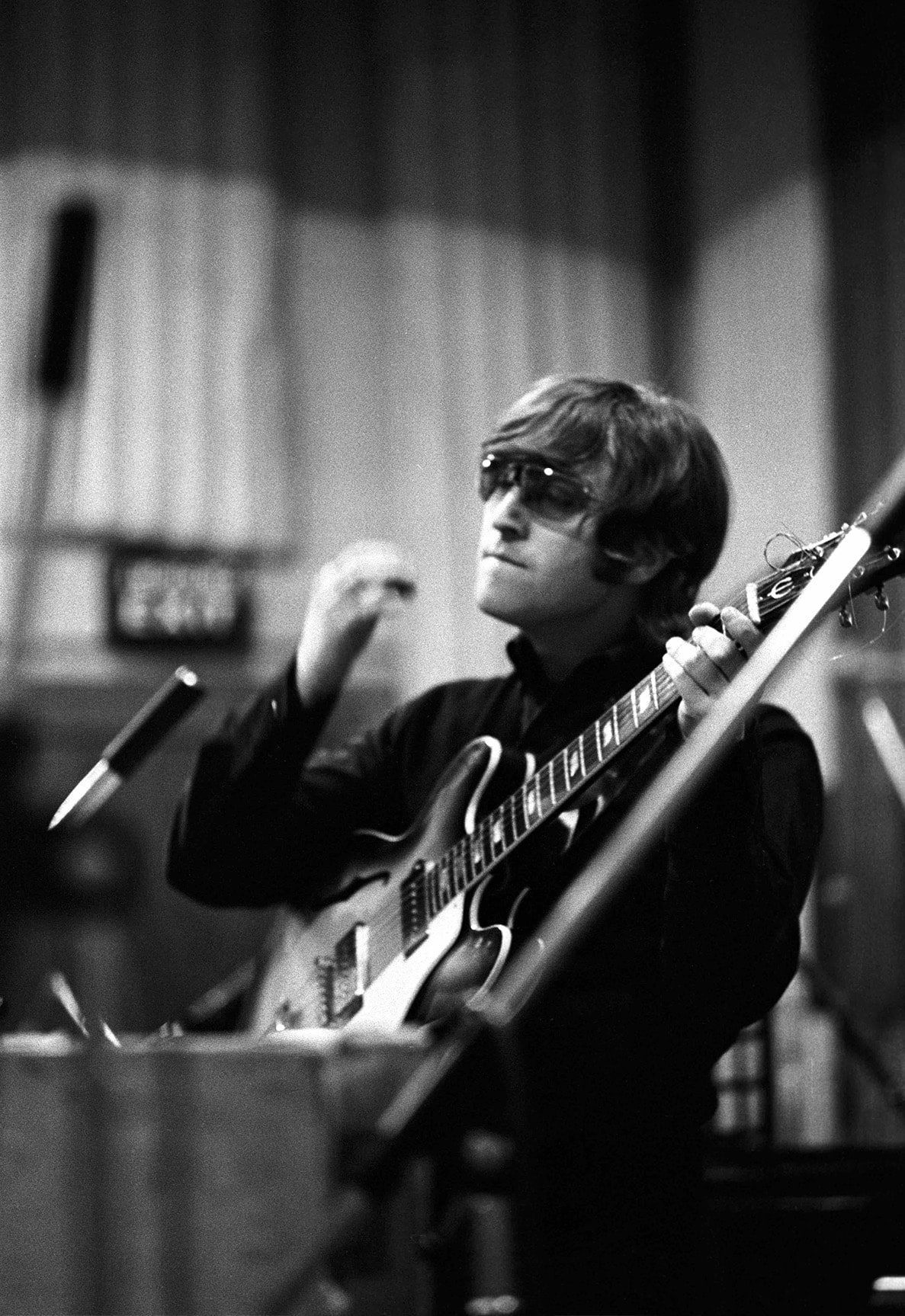

A4 – A second sitar and fuzz guitar are overdubbed. (Some sources state George played this fuzz guitar. Jerry Hammack in The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2 states that George used either the “1961 Fender Stratocaster with a synchronized tremolo, [the] 1964 Gibson SG Standard with Gibson Maestro Vibrola vibrato, [or the] 1965 Epiphone ES-230TD.” (p. 114) Other sources have indicated that John Lennon might have played the fuzz guitar here.)

Furthermore, Winn tells us that on this same day, “a 34-second edit piece was taped for the song’s intro, consisting of…sitar. At the end of the day, a rough mono mix of take 6 was made for George to take home.” (p. 9)

Date Recorded: 13 April 1966

Time Recorded: 2:30 p.m. – 6:30 p.m.

Studio: EMI Studios, Studio 3

Tech Team

Producer: George Martin

Balance Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Richard Lush (In his Beatles Recording Sessions, Lewisohn notes, “Eighteen-year-old Richard Lush, another Abbey Road apprentice with a promising future, made his recording session debut as Beatles tape operator on this day.” p. 73)

On the 13th, take 6 was reduced to take 7 as A1 and A2 were combined. Then, A3 and A4 were combined. (Winn, That Magic Feeling, 9)

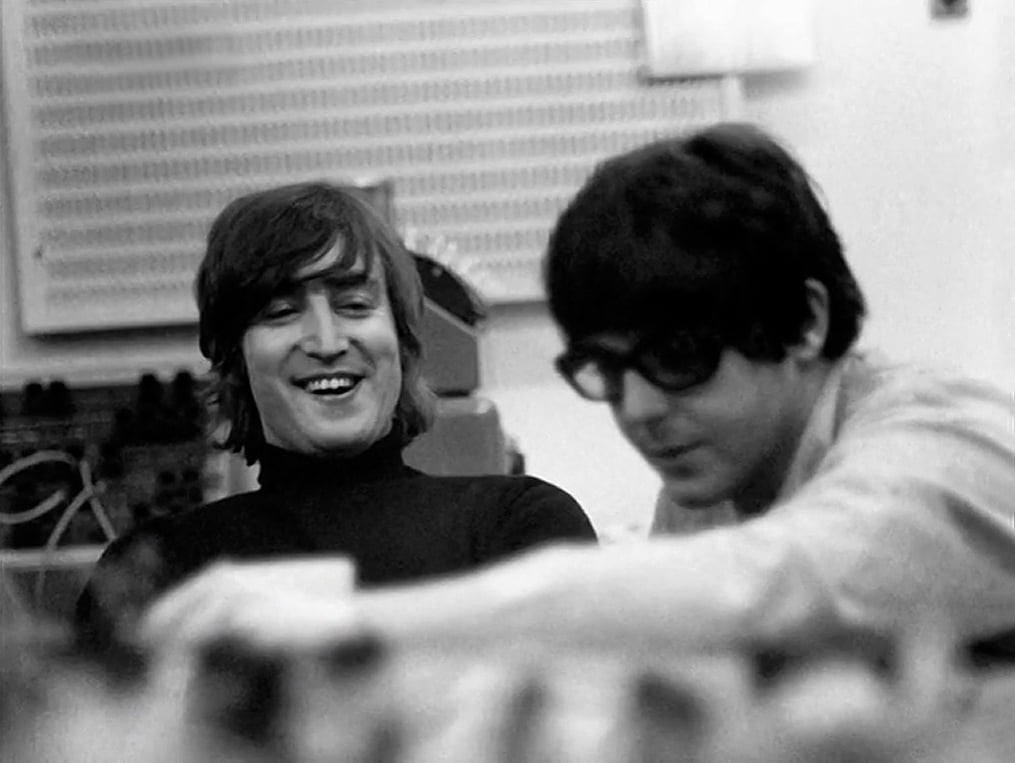

Paul then added a new tape on which he sang high harmony on the lines, “They’ll fill you in with all their sins you’ll see.” (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 73). However, both Lewisohn and Rodriguez tell us that Paul’s high harmony part eventually “fell by the wayside.” (Rodriguez, Revolver: How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, 114)

Also, on the 13th, Ringo played the tambourine.

Date Recorded: 25 April

John C. Winn informs us that the 34-second intro piece was added to “Love You To” on this day.

Editing was done on 20 June and 21 June. During this time frame, George Harrison decided on the title of “Love You To,” supplanting its working title (supplied by Geoff Emerick) of “Granny Smith” – Emerick’s favorite apple. (Winn, 9 and Emerick, 123)

Instrumentation and Musicians:

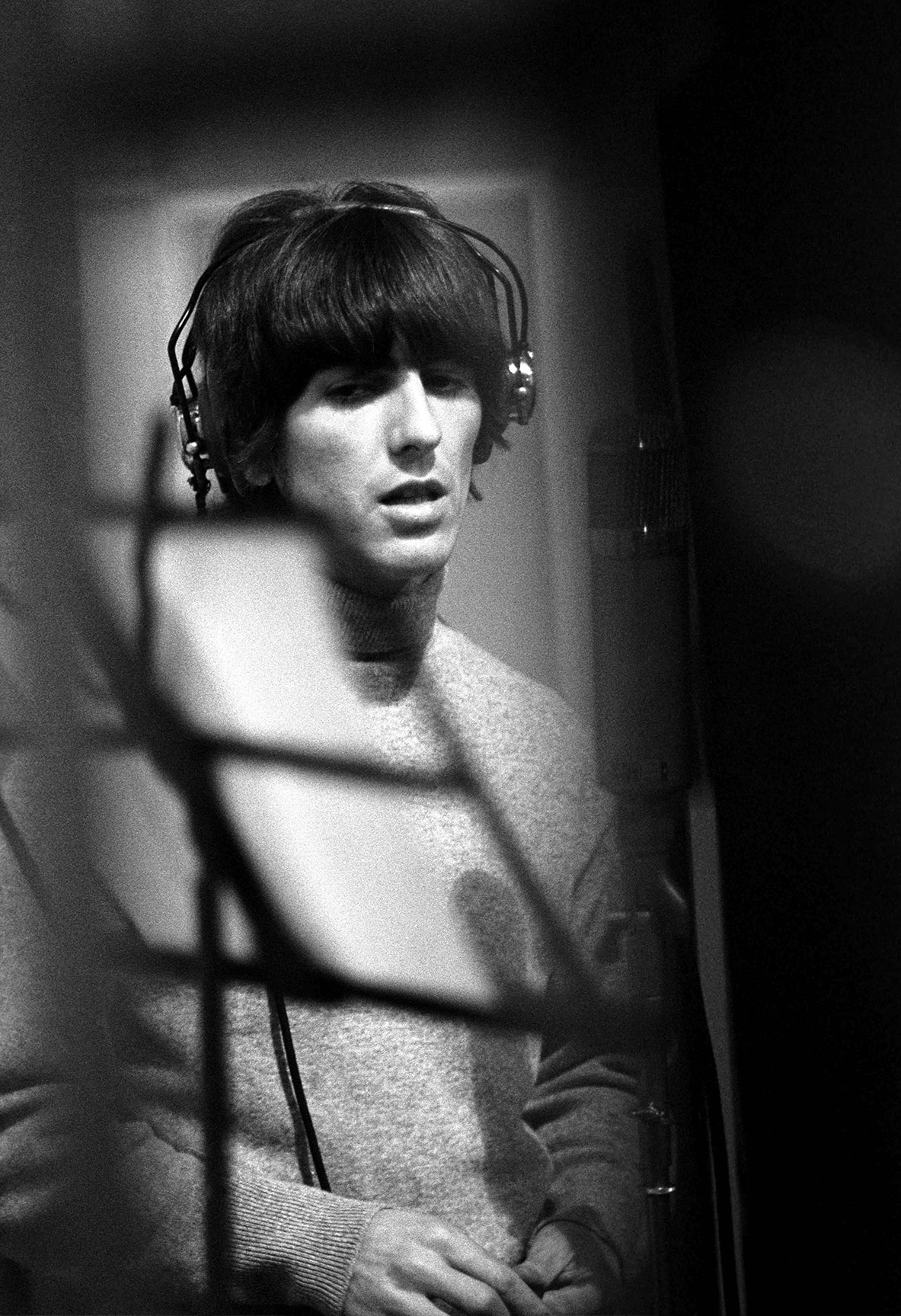

George Harrison, the composer, sings lead vocals and plays an acoustic guitar, an electric guitar, and possibly, the sitar. (Some music critics question the latter. In Revolution in the Head, for example, Ian MacDonald states that a “sitarist [is]now thought to have played most of what was attributed to Harrison.” p. 155).***

Paul McCartney plays bass on his 1964 Rickenbacker 4001S bass in the early stages of the song and possibly provides backing vocals.

Ringo Starr plays tambourine.

Anil Bhagwat plays tabla.

***Note from Susan Shumsky: Anil Bhagwat swears that George played the sitar throughout.

Ayana Deva Anagadi on sitar. (Womack, Long and Winding Roads, 139)

Several other accomplished musicians from the North London Asian Music Circle play tambura.

Sources: The Beatles, The Anthology, 209, Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 217, Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 72-73, Shumsky, The Inner Light: How India Influenced The Beatles, 69-77, Spizer, The Beatles Rubber Soul to Revolver, 216, Rodriguez, Revolver, How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, 66-67 and 114-115, Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 113-114, Everett, The Beatles as Musicians, 40-42, Margotin and Guesdon, All the Songs, 330-331, Winn, That Magic Feeling, 9-10, Emerick, Here, There, and Everywhere, 123-124, Turner, A Hard Day’s Write, 106, Turner, Beatles ’66, 147-149, Riley, Tell Me Why, 186, MacDonald, Revolution in the Head, 155, Womack, Long and Winding Roads: The Evolving Artistry of The Beatles, 139-140, and Hunter Davies, The Beatles Lyrics, 156-157.

What’s Changed:

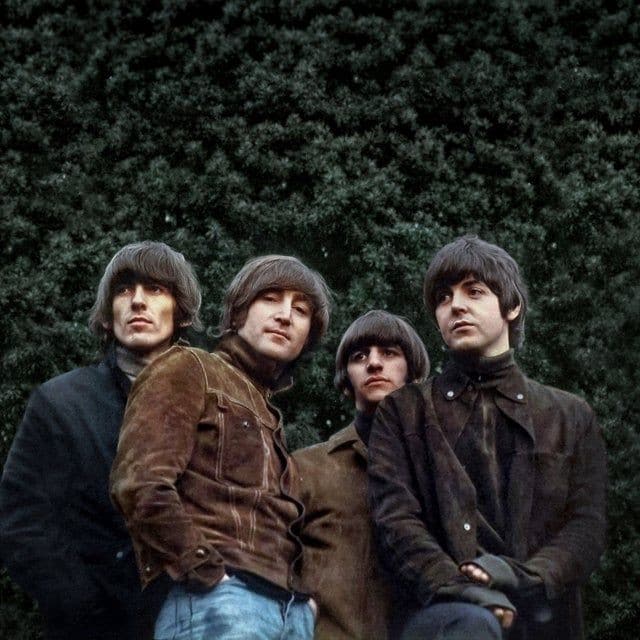

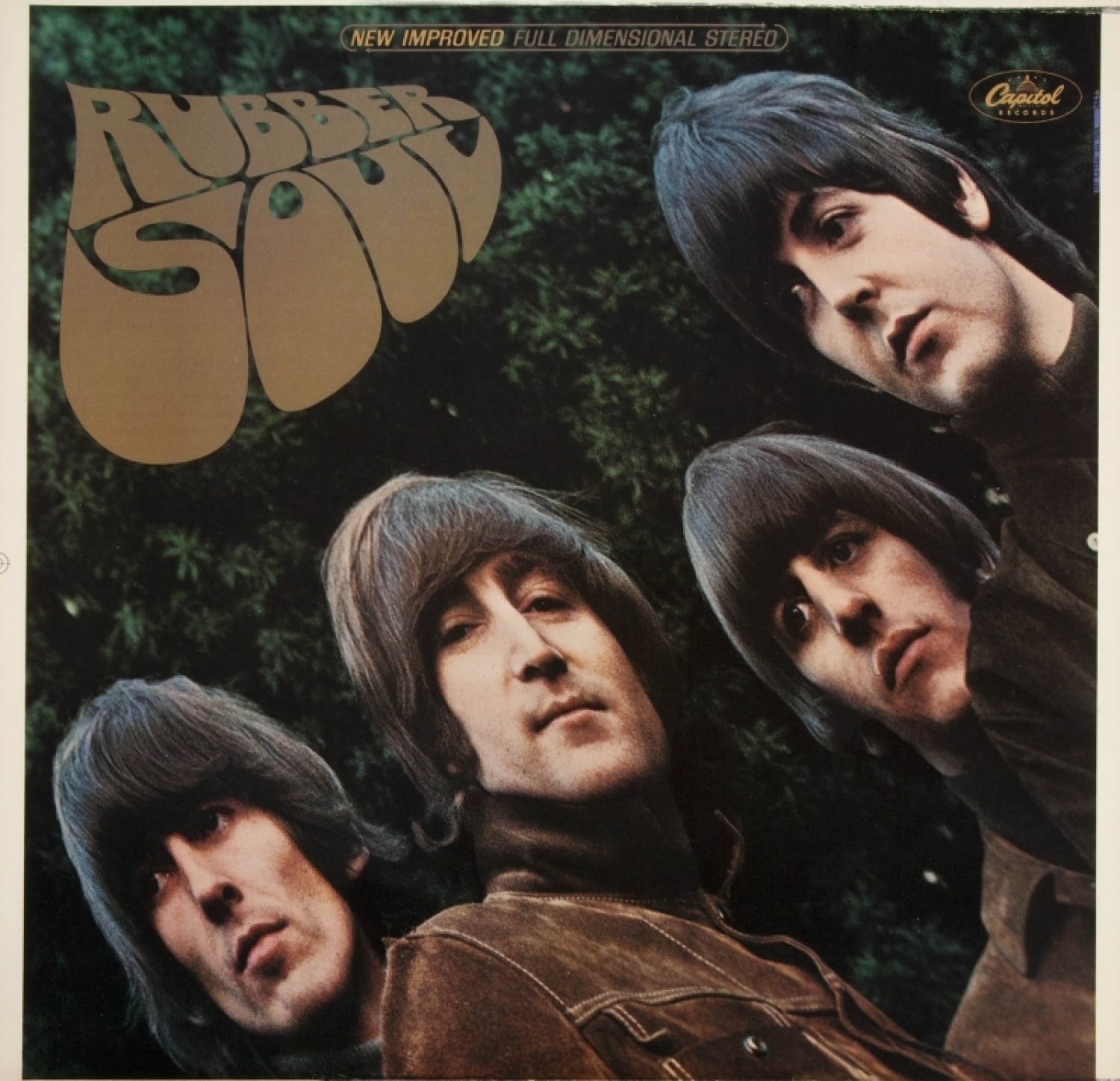

The better topic to address might be “What Hasn’t Changed?” In this fourth track on Revolver, nothing is familiar!!! No guitars, no drums, no standard four-chord rock progression. Everything we thought we knew about The Beatles has altered. Let’s take a look:

- A Second Harrison Track on Side One – Gone are the days of the obligatory “one-track-per-album” Harrison allotment. On Revolver, not only does George perform three songs, but he also scores the opening track! And here, George comes back strong with a second original offering for Side One, even though Lennon and McCartney have, thus far, performed only one song each.

In his book Here, There, and Everywhere, EMI Engineer Geoff Emerick observed, “I noticed a definite maturing of George Harrison during the course of the Revolver sessions. Up until that point, he had played a largely subordinate role in the band…But he ended up recording three original songs on this album.” (p. 125)

- The “Integration of Foreign Musical Cultures” – Tim Riley uses these words to quantify the unique sound of Harrison’s second track on Revolver. Riley goes on to say, “It’s a bold move from [George], trading in the religion of Chuck Berry’s guitar for Ravi Shankar’s meditative sitar.” (Tell Me Why, 186)

Bold move, indeed! For most fans, the melody of “Love You To” was utterly alien. As Hunter Davies aptly observes in The Beatles Lyrics, “The shock of the music – to our naïve, primitive, virgin 1966 ears, accustomed to guitar-based rock’n’roll – rather overshadowed the words. And it still does.” (p. 156)

“Love You To” was replete with instruments that Beatles fans had never heard. Yes, there had been a bit of sitar in “Norwegian Wood,” but a glimpse only. Now, Harrison was introducing the tabla and tambura. On a grander scale, even the tone, meter, and musical progression of “Love You To” sounds unusual to untrained Western ears. Harrison truly was stepping out – introducing not just a new song but a revolutionary new genre and a new way of thinking!

- Emerick’s Revolutionary Close-Miking of the Tabla – In Emerick’s own words, “I had never miked Indian instruments before, but I was especially impressed with the huge sound coming from the tabla (percussion instruments similar to bongos). I decided to close-mic them, placing a sensitive ribbon-mic just a few inches away, and then I heavily compressed the signal. No one had ever recorded a tabla like that – they’d always been miked from a distance. My idea resulted in a fabulous sound, right in your face….” (Here, There, and Everywhere, p. 125)

The employment of the ribbon-mic, Jerry Hammack explains, was radical in and of itself. He says, “As another departure from Norman Smith’s recording techniques, ribbon microphones wouldn’t normally be used in close proximity as they were sensitive to rapid changes in air pressure such as those created by a drum (the tabla being a pair of hand drums)….” (The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 113) Even the recording techniques of “Love You To” issued in a new era at EMI.

- A Dramatic Change of Meter – As “Love You To” nears its close, the meter decidedly changes pace, a sound that Walter Everett tells us “was a normal event for Indian listeners.” But for Western ears, this accelerated whirlwind of sound was “something entirely different.” (The Beatles as Musicians, 40) This change of pace would begin to influence John’s songs within just a few weeks, Everett states. After being largely ignored for a few years, George Harrison was now emerging as a trendsetter.

- A Change of Attitude – Music experts point out that many of Harrison’s early songs express a mistrustful, “leave-me-alone” attitude. As Robert Rodriguez observes in Revolver, How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, “Thematically, George’s material [before Revolver] tended toward conveying disapproval (“Don’t Bother Me,” “You Like Me Too Much,” “Think For Yourself”) – not usually the stuff of which pop hits were made.” (p. 66)

Yet, here in “Love You To,” Harrison’s newfound interest in Indian music and religion seems to have altered his course. As a lifelong pragmatist, George is still fully aware that “each day just goes so fast/You turn around it’s past.” But Harrison’s reaction to the fleeting nature of existence is no longer depression or resentment. Instead, George wants to celebrate each day with song and love-making: “Make love all day long! Make love singing songs!”

Furthermore, although George is still conscious of the fact that:

“There’s people standing round

Who’ll screw you in the ground,

They’ll fill you in with all their sins, you’ll see…”

George opts to ignore those individuals…to take the high road and live a life full of passion and celebratory music. He isn’t oblivious to reality; he has learned to cope with life’s downside in a new and positive way.

A Fresh, New Look:

Jude Southerland Kessler: Susan, for years, Beatles music experts have told us about unique elements in this song that made it very special. But most people – unfamiliar with the terms these experts used – still didn’t understand exactly what was happening in the song musically. So, if you don’t mind, please walk us through what these terms mean and how they relate to “Love You To.”

Susan Shumsky:

Sitar – Indian musical instruments were played on the soundtrack of The Beatles movie Help!, a parody about ancient Indian highway robbers and murderers called “thuggees.” The first time George Harrison encountered the sitar was in Twickenham Studios while filming Help! in February 1965. He described, “We were waiting to shoot the scene in the restaurant when the guy gets thrown in the soup, and there were a few Indian musicians playing in the background. I remember picking up the sitar and trying to hold it and thinking, ‘This is a funny sound.’” (Havers, “The Making of George Harrison’s ‘Within You Without You,’” Udiscovermusic.) Later that year, Jim McGuinn and David Crosby of The Byrds introduced George to the music of Indian sitar virtuoso Pandit Ravi Shankar. Soon afterward, George visited Indiacraft, a shop in London on Oxford Street, where he purchased a second-rate sitar, which he plucked on the song “Norwegian Wood.”

George said, “When I first heard Indian music, I just couldn’t really believe that it was so, so great. And the more I heard of it, the more I liked it. And it just got bigger and bigger, like a snowball.” (D’Silva, The Beatles and India, directed by Ajoy Bose and Peter Compton, Renoir Pictures). “You can get so much more out of it if you are prepared really to concentrate and listen. I hope more people will try to dig it.” (Beatles and Roylance, The Beatles Anthology, 209)

“Love You To” was the first song George wrote for Indian musical instruments. He said, “The sitar sounded so nice and my interest was getting deeper all the time. I wanted to write a tune that was specifically for the sitar.” (Beatles and Roylance, The Beatles Anthology, 209)

Sitar is a stringed Indian instrument of the lute family. About four feet long, it has a deep pear-shaped gourd body; a long, wide, hollow wooden neck; metal strings, and both front and side tuning pegs. There are usually five melody strings, one or two drone strings that accentuate the rhythm, and up to 13 sympathetic strings beneath the frets that are not played by the performer but resonate in sympathy with the playing strings, creating a polyphonic timber. Twenty arched movable convex metal frets are tied along the neck. Musicians pluck the strings with a wire plectrum on the right forefinger while the left hand presses or pulls the strings with subtle pressure on or between the frets.

Today, sitar is the dominant instrument in Hindustani music; it is played as a solo instrument and in ensembles with tambura (drone lute) and tabla (drums). George Harrison popularized the sitar in the West because he studied with Ravi Shankar.

Sitar is played on the following Beatles records: “Norwegian Wood,” “Love You To,” and “Within You Without You.” In George’s solo career, sitar appeared on many of his albums, usually played by Ravi Shankar.

After George gave up recording songs with sitar, he began imitating sitar sounds by playing glissando riffs on a slide guitar. A few samples include “My Sweet Lord,” “Wah Wah,” “I Dig Love,” “Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth),” “Someplace Else,” “Free as a Bird,” “Marwa Blues,” Lennon’s “How Do You Sleep,” Badfinger’s “Day After Day,” and Ringo’s “Back Off Boogaloo.”

Tabla – The tabla is two drums (bass and snare) played by one performer. Both drums have compound skins onto which a black paste of flour, water, and iron filings, called siyahi, is added to alter the resonance frequency. The smaller, higher-pitched drum is the dayan, usually made of heavy lathe-turned rosewood. The larger drum, called bayan, is made of metal or pottery. An off-center siyahi on the bayan allows the performer to vary the pressure, changing the pitch with the palm while striking with the fingertips.

The first time that tabla appeared on a Beatles song was “Love You To.” It is also played on “Within You Without You.” Tabla tarang (an ensemble of 10 to 16 dayan drums—each tuned to a different note) is heard on “The Inner Light.” Tabla was played widely in George Harrison’s post-Beatles projects and was also used by other solo Beatles.

Tambura – The tanpura or tambura is a long, four-stringed fretless lute made of light hollow wood, with either a wood or gourd resonator. Tambura typically plays the background rather than the melody. It accompanies, supports, and blends with the tones sung or played on the lead instruments and/or vocals by providing a continuous harmonic drone. The tambura player plucks the strings in a continuous loop rather than in rhythm with the piece. This repeated cycle is the sonic canvas on which the melody is painted.

Tambura is played on the following Beatles records: “Love You To,” “Within You Without You,” “Tomorrow Never Knows,” “Getting Better,” and “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” George sometimes used a harmonium or organ as a drone instrument to mimic the tambura, most notably on “Blue Jay Way.”

Swarmandal – Although some noted sources have stated that Swarmandal (a plucked box zither) was used in “Love You To,” it was not played on this song. It is played on the following Beatles records: “Within You Without You” and “Strawberry Fields Forever.”

Sitarist Ted Morano (see below re. his bio) told me: “The only error that I found in your book The Inner Light is the mention of swarmandal being used on the track ‘Love You To’ (the glissando that opens the track). That is not a swarmandal, it is the taraf (sympathetic) strings on the sitar. The taraf strings are 11-13 strings that run under the frets, and are tuned to the raga being performed. It is common for a sitarist to strum the taraf strings at the beginning of a performance.

“Here are examples from Ravi Shankar recordings:

Khyal – Although some sources state that “Love You To” was George’s first khyal, this style is not really relevant to the song “Love You To.” In khyal, the vocalist and instrument, such as sarangi (Indian violin) or harmonium, play the same melody in heterophony. George tried to copy the khyal style on the echoing parts of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” (starting with “cellophane flowers,” etc.). George said, “For ‘Lucy’ I thought of trying that idea [of melody played in unison with voice], but because I’m not a sarangi player, I played it on guitar along with John’s voice. I was trying to copy Indian classical music.” (Beatles and Roylance, The Beatles Anthology: www.beatlesebooks.com/lucy-in-the-sky.) George was also inspired by Khyal in “Within You and Without You,” where dilruba (an Indian cello similar to sarangi) mirrored the same melody as George’s vocal, note for note.

Kessler: Susan, we know that George Harrison requested that the North London Asian Music Circle accompany him in performing the melody of “Love You To.” Tell us more about them, please.

Shumsky: In 1946, Indian writer and activist Ayana Angadi and his British wife Patricia Fell-Clark founded the Asian Music Circle (AMC), at their home in Fitzalan Road, Finchley, North London. The organization promoted Asian arts and culture. Inspired by meeting Ravi Shankar in India, American violin virtuoso Yehudi Menuhin became president of AMC in 1953. By inviting B. K. S. Iyengar (founder of Iyengar Yoga) to teach at AMC, Menuhin introduced yoga to Britain.

In 1955, AMC hosted the first classical Indian music concerts in the West at the “Living Arts of India Festival” in New York, which introduced Ali Akbar Khan (on sarod), Ravi Shankar (Khan’s brother-in-law, on sitar), and Vilayat Khan (on sitar). This led to the first Indian music album in the West: Music of India: Morning and Evening Ragas (Angel 1955), and to Ravi Shankar’s popularity in the jazz community.

George Martin, staff producer at EMI’s Parlophone Records, had previously gotten referrals from AMC’s Ayana Angadi to hire local Indian musicians for film and recording work. In 1962, Martin began working with The Beatles when they signed with Parlophone. Under Martin’s influence, their film Help! featured an Indian-themed script and musicians.

As George Harrison was playing sitar on “Norwegian Wood” in the recording studio on October 21, 1965, a string broke. Martin suggested contacting Ayana Angadi for a replacement. Ringo made the phone call and Angadi’s daughter asked loudly, “Ringo who?” Angadi rushed to the phone, and then brought the string, along with his wife and four children, to EMI’s Abbey Road Studios, to watch The Beatles record. (Newman, Abracadabra! The Complete Story of the Beatles’ Revolver, 23.)

For the next six months, George and Pattie spent every weekend at the Angadi home, immersed in Indian music. They attended recitals at AMC and watched Ravi Shankar perform at the Royal Festival Hall. (Turner, Steve. Beatles ‘66: The Revolutionary Year) With enthusiasm to master sitar, George began studying with an AMC sitar player. (Rodriguez, Robert. Revolver: How the Beatles Reimagined Rock ’n’ Roll, 114)

Kessler: Robert Rodriguez, in Revolver: How The Beatles Re-imagined Rock’n’Roll, tells us, “Some believe that the apparent complexity heard on ‘Love You To’ was beyond [George’s] capabilities, at least in spring 1966. But others point to his single-minded diligence in mastering the instrument [the sitar], as well as his study through private lessons, proximity to accomplished musicians, and close listening to pertinent records.” Where do you stand in this discussion? Do you think George ceded most of the responsibility to the North London Asian Music Circle, or could he function as lead performer?

Shumsky: Ted Morano earned an MFA Degree in North Indian Classical Music, Sitar performance, from the California Institute of the Arts. He is a master at sitar, surbahar, tabla, dilruba, pakhawaj, and tambura, a dhrupad vocalist, and a highly respected Indian music teacher. He performed “Within You, Without You” and “The Inner Light” many times with the Beatles Magical Orchestra and other groups (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cTG7M6sEZfQ). He also recorded the dilruba tracks for “Within You, Without You” for Geoff Emerick as part of his “The Sessions” show.

After the remix of Revolver was released, Ted concluded that George was definitely the sole sitarist on “Love You To.” He said, “The 2022 remixed edition of Revolver has excellent sound quality, and this clarity makes it easier to hear the different layers in the song. Now it is easy to hear that George double-tracked sitar on the main riff, to give it a bigger sound. The way George strums the sitar strings at the start of his brief alap, and also plays harmonics, is not characteristic of how a trained Indian sitarist would play. The structure of his solo later in the song is also not how a trained Indian sitarist would play. Most revealing was hearing the mono mix of the song, which is several seconds longer than the stereo version, and George can be heard in the fade-out playing several figures which, while very musical and creative, are not something that a trained Indian sitarist would play.

Morano goes on to say: “More important info came to light regarding the sitar that George used on the recording. It is not the same sitar that is used on ‘Norwegian Wood.’ George obtained a better sounding and playing instrument after the recording of Rubber Soul. According to Pattie, he spent most of their honeymoon obsessively practicing sitar. Although this was before he began learning from Ravi Shankar, he did receive some basic instruction in London that enabled him to make significant progress on his own. This can clearly be heard on ‘Love You To.’”

Kessler: Similarly, Harrison selected a distinguished percussionist, Anil Bhagwat, to perform with him on the track. Give us some background info about this notable musician, if you don’t mind.

Shumsky: “Love You To” was the first pop song to present Indian music in an authentic classical Hindustani structure and arrangement, which earned George the title “The Mystic Beatle.” George’s hypnotic, drone-like vocals augmented the Indian effect. For the recording session on April 11, 1966, George hired unidentified musicians referred by the Asian Music Circle to play the Indian music track. Instruments on the track included sitar, tabla, and tambura.

Anil Bhagwat was hired to play tabla—the first time that tabla ever appeared on a Beatles song. Bhagwat recalled, “Angadi called and asked if I was free that evening to work with George. He didn’t say it was Harrison. It was only when a Rolls Royce picked me up that I realized I’d be playing on a Beatles session.

“When I arrived at Abbey Road, there were girls everywhere with Thermos flasks, cakes, sandwiches, waiting for The Beatles to come out.” “George told me what he wanted and I tuned the tabla with him. He suggested I play something in the Ravi Shankar style, sixteen-beats, though he agreed that I should improvise. Indian music is all improvisation. It was one of the most exciting times of my life.” (Womack, The Beatles Encyclopedia: Everything Fab Four, 310)

Other than Anil Bhagwat, AMC musicians that performed on “Love You To” have never been identified. However, Bhagwat claimed, “I can tell you here and now—100 percent it was George on sitar throughout.”

In my book The Inner Light: How India Influenced The Beatles, I quoted sitarist Ted Morano as saying that to strengthen what George played, another sitarist probably overdubbed the main melody and also played the fadeout at the end. However, on November 25, 2022, Morano changed his mind: “It is a fortuitous coincidence that the new Revolver editions also came out this week. There is a lot of Beatle frenzy right now. In fact, after listening to the clearer mix, and the out-take of George rehearsing ‘Love You To,’ I am convinced that it is only George playing sitar. There were no overdubs by another sitarist.”

Kessler: In The Beatles Lyrics, Hunter Davies observes, “The shock of the music – to our naïve, primitive, virgin 1966 ears, accustomed to guitar-based rock’n’roll – rather overshadowed the words.” Agree or disagree? And is this true today, do you think?

Shumsky: I agree that the intensity of the double-tracked Indian music and the relentless beat of the tabla were probably quite a shock to Western ears, and it overshadowed the song’s lyrical message. In fact, double-tracking Indian music had never previously existed in India, so it would have even been a shock to Indian ears. I feel that few people listening to this song paid attention to the lyrics, as they were trying to accustom to what they probably perceived as deafening, strange sounds of cacophonous instruments.

Kessler: Finally, what is the message of this song? To me, it’s equivalent to Robert Herrick’s 1648 poem, “To the Virgins, To Make Much of Time,” with a shot of inspiration from John Lennon’s line in “Dizzy Miss Lizzy”: “Love me ’fore I grow too old!” Or, as Ken Womack suggests, it’s about “the fleeting nature of existence.” (Long and Winding Roads: The Evolving Artistry of The Beatles, 139) Yet, Tim Riley asserts the lyrics are about “the Eastern philosophy of time as a dimension to be passed through.” (Tell Me Why, 186) What’s going on in this song? Is it about all of one of these things, some, or none? Do tell.

Yes, I feel that “Gather ye rosebuds while ye may” conveys a similar message as “Love you To.” This idea of the ephemeral nature of our physical world, along with the urgency to make the most of every moment, parallels both Herrick’s poem and George’s lyrics. He often sang about the fleeting duality of the material world and its contrast with the eternal oneness of the spiritual world. On the physical plane, “all things must pass.”

Also, in the context of 1966, during which this song was composed, The Beatles were influenced by the psychedelic Flower Power philosophy of “Make Love, Not War,” espoused by San Francisco hippies at the time. This slogan became the cornerstone of hippie philosophy. The message of “Love You To” swings from free love and the embracing of spiritual awakening to cynicism and the rejection of materialistic society.

Indian philosophy tells us that material life is not permanent and therefore not real. This corporeal body we temporarily inhabit is not our true eternal nature. Attachments to the physical plane bind us to chains of ignorance. Only one thing is eternal. It is not the material world. It is the unmanifest consciousness, beyond space, time, and causation.

We believe ourselves to be our physical body, thoughts, feelings, intellect, ego, or experiences. But that is not who we really are. We are the unbounded, undifferentiated radiance of Brahman—pure consciousness. Divine love, free from ego attachment, is key to letting go of material bonds. By embracing the simplicity of pure love, we realize our true divine nature—absolute bliss consciousness (satchitananda), beyond the physical. It is never born and never dies.

For more information on Susan Shumsky or her new book, The Inner Light: How India Influenced The Beatles, HEAD HERE and HERE

Follow Susan on Facebook HERE and on Twitter HERE

Come meet Susan in person at The Chicago Fest for Beatles Fans, Hyatt Regency O’Hare, August 11-13, 2023!