Side Two, Track Two

In Which “You Don’t Get Me” becomes “And Your Bird Can Sing”

by Jude Southerland Kessler and Erin Torkleson Weber

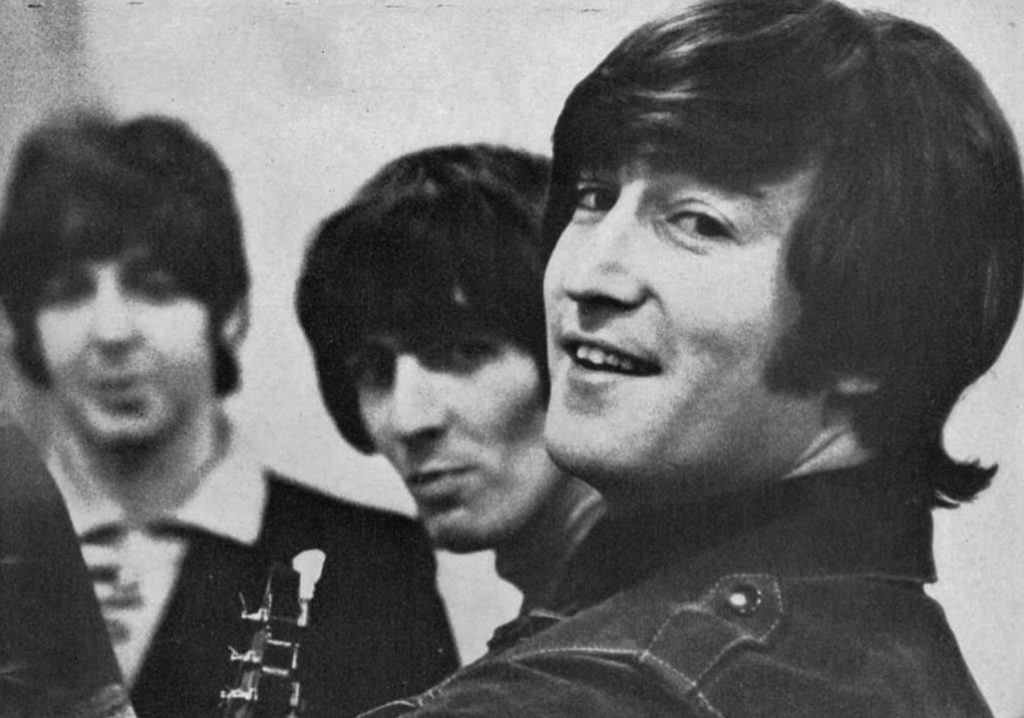

This month, our Fest Blog continues our in-depth study of Revolver with a song that has “more than meets the eye.” It’s John Lennon’s enigmatic “And Your Bird Can Sing,” a track full of vitriolic lyrics, incredible musicianship, and controversy about “who did what.”

Joining Jude Southerland Kessler, author of The John Lennon Series this month to explore this song is the highly respected author Erin Torkelson Weber. A graduate of Newman University and Wichita State, after completing her graduate degree, Erin Weber began teaching American History part time at Newman University. Looking for a new, more modern subject to appeal to students in her senior seminar and research classes, Erin, a Beatles fan since childhood, began researching the band’s historiography. In 2016 McFarland published her work The Beatles and the Historians: An Analysis of Writings About the Fab Four, which examines the historical methodology and historiographical arc of the Beatles story. In addition, Erin helps run a blog, “The Historian and the Beatles,” which provides book reviews and source analysis of various Beatles works: she also co-hosts “All Together Now,” a podcast with Karen Hooper, and has guest starred on numerous other podcasts. Erin is a beloved member of our Fest Family, and we welcome her to the blog!

What’s Standard:

Date Recorded: 20 April 1966

Time recorded: 2.30 p.m. – 2.30 a.m. (Note: Lewisohn points out that also recorded on this long day in studio were 4 rhythm track takes of “Taxman.”)

Technical Team:

Producer: George Martin

Sound Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil MacDonald (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 75)

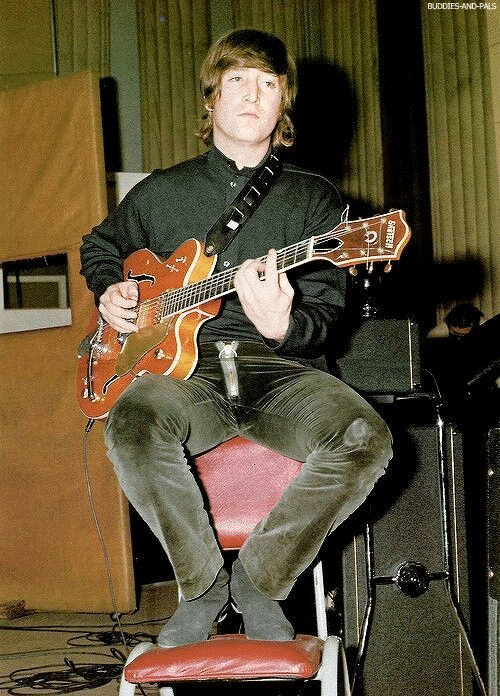

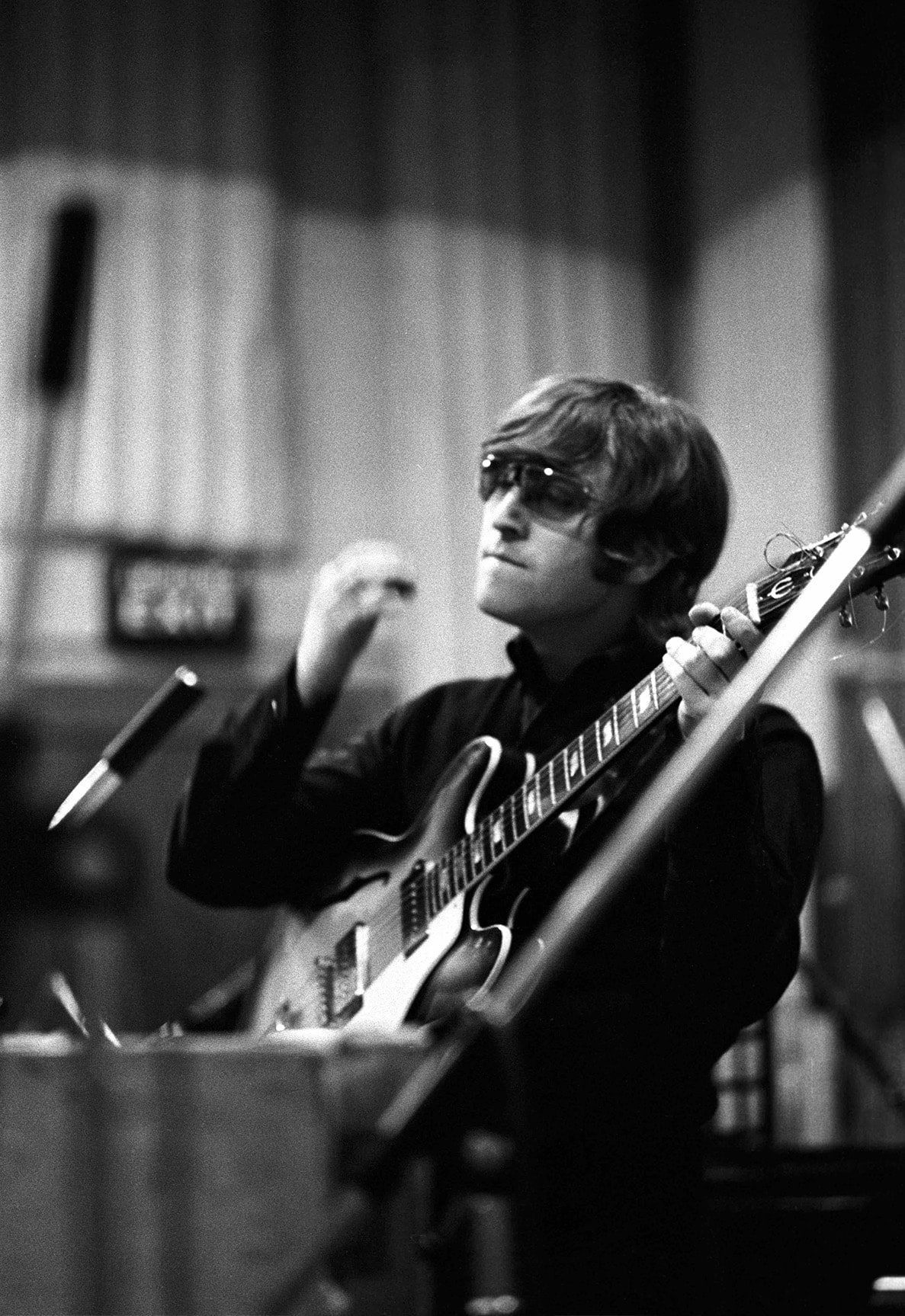

On this day: A backing track was created with Ringo on his 1964 Ludwig Oyster Black Pearl “Super Classic” drum set and George on his 1965 Rickenbacker 360 12-string electric. There is a second guitarist, and the identity of that person has been questioned and debated through the years. In The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, Hammack states that it was “either Lennon on his 1961 Fender Stratocaster with synchronized tremolo or McCartney on his Epiphone ES-230TD, Casino electric guitar with Selmer Bigsby B7 vibrato.” (p. 125) Hammack notes that when George Harrison was quizzed about who performed on the second guitar by Guitar Player magazine in 1987, Harrison admitted that he didn’t know the answer. Hammack says that he feels “Lennon’s aggressive count-in indicates him as the guitarist,” but there is no conclusive proof. On this same track, John and Paul also sang on the backing vocals. (Hammack, 125)

Two takes were performed. Take Two was deemed “best.”

Then, superimpositions followed:

McCartney performed on his 1964 Rickenbacker 4001S bass

Harrison performed a guitar solo on one of 3 guitars he had in studio

Starr performed on tambourine

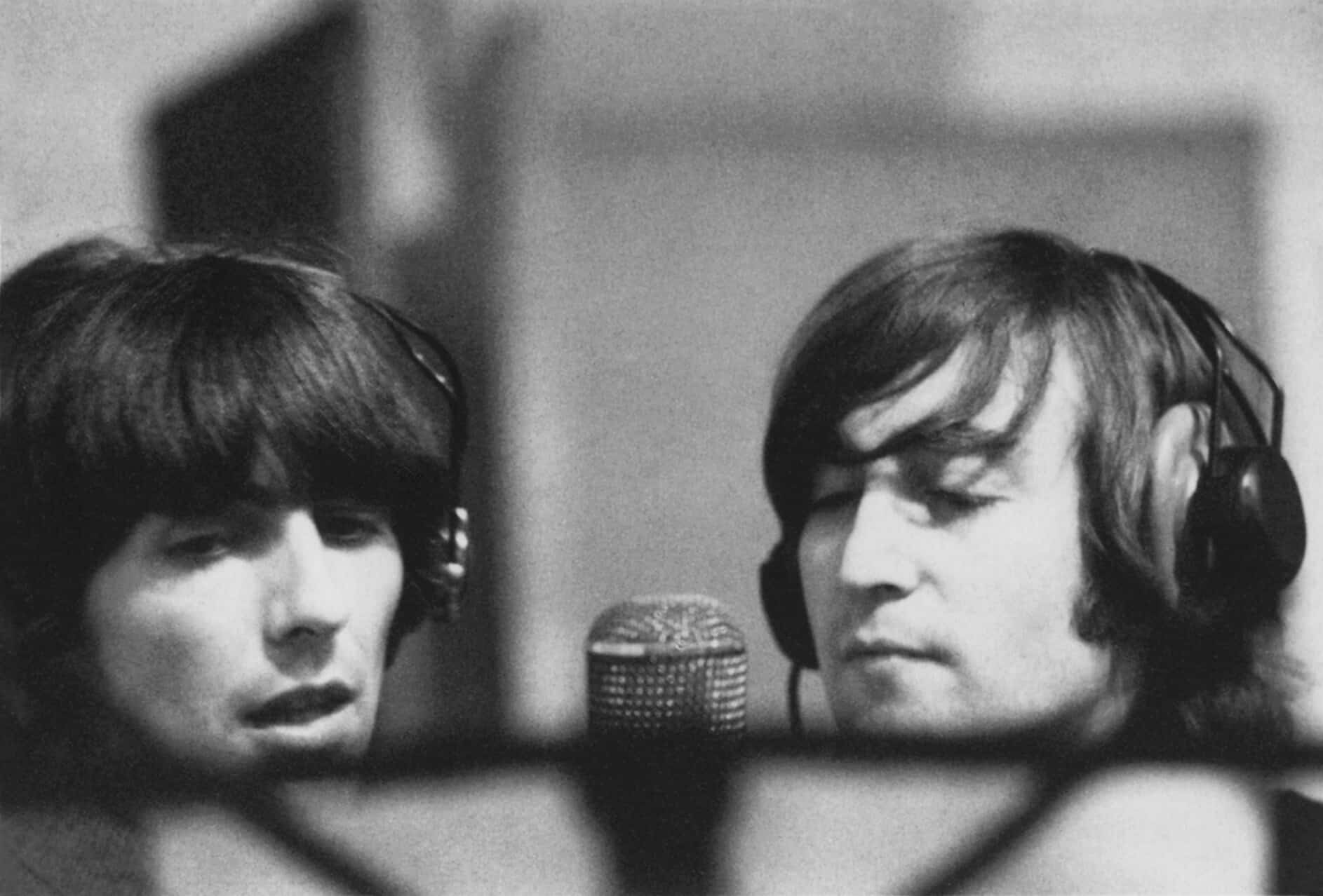

Paul and John double-tracked the backing vocals. The harmonies in the backing vocals are quite intricate and of note. This often-overlooked song has many layers.

Date Reworked: 26 April 1966

Location for both sessions: EMI, Studio Two

Time recorded: 2.30 p.m. – 2.45 a.m.

Technical Team:

Producer: George Martin

Sound Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil McDonald (Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 76)

On this day: The Beatles decide to completely remake “And Your Bird Can Sing.” In 11 takes, (which are numbered 3-13) The Beatles create a completely new backing track. Hammack tells us that “Lennon [is] either on his Fender Stratocaster or his Epiphone ES-230TD, Casino electric guitar, Harrison [is] again on [his] Rickenbacker 360-12 electric guitar, McCartney [is] on his Rickenbacker 4001S bass, and Starr is on his Ludwig drums. (Hammack, 126)

Takes 6 and 10 were selected as “best.” Superimpositions included:

Ringo on tambourine

Ringo on high-hat and cymbals

Eventually, Take 10 would be chosen as “best,” but Paul’s bass work on Take 6 would still be dubbed as the best. So, these elements were blended.

Once again, the harmony lead guitar work is questioned. There is no doubt that Harrison performed. But no one knows for sure if Lennon or McCartney accompanied him.

As the last order of business, Hammack tells us, “Finally, John added his lead vocals with McCartney and Harrison on backing vocals and hand claps (all recorded with frequency control (varispeed) at slower than normal tape speed, on playback sounding around half a semitone higher in pitch.)” (The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, p. 127)

***See Jerry Hammack’s The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 125-128 for more information.

Other Valuable Sources: Lewisohn, The Beatles Recording Sessions, 75 and 77 , Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 218 and 219, Winn, That Magic Feeling, 12-13 and 14-15,Lennon, Cynthia, A Twist of Lennon, 128, Rodriguez, Revolver: How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, 89 and 123-126, Robertson, The Art and Music of John Lennon, 54-55, Gould, 360, Spizer, The Beatles for Sale on Parlophone Records, 215, Spizer, The Beatles Rubber Soul to Revolver, 219, Turner, Beatles ’66, 159-161, Turner, A Hard Day’s Write, 111-112, Margotin and Guesdon, 340-341, Davies, The Beatles Lyrics, 169-171, Spignesi and Lewis, 79-80, Riley, Tell Me Why, 192-193, MacDonald, Revolution in the Head, 159, Womack, Long and Winding Roads (2007 edition), 143-144, Womack, The Beatles Encyclopedia, 36-37, Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 125-128, and Mellers, Twilight of the Gods, 76.

A Fresh New Look:

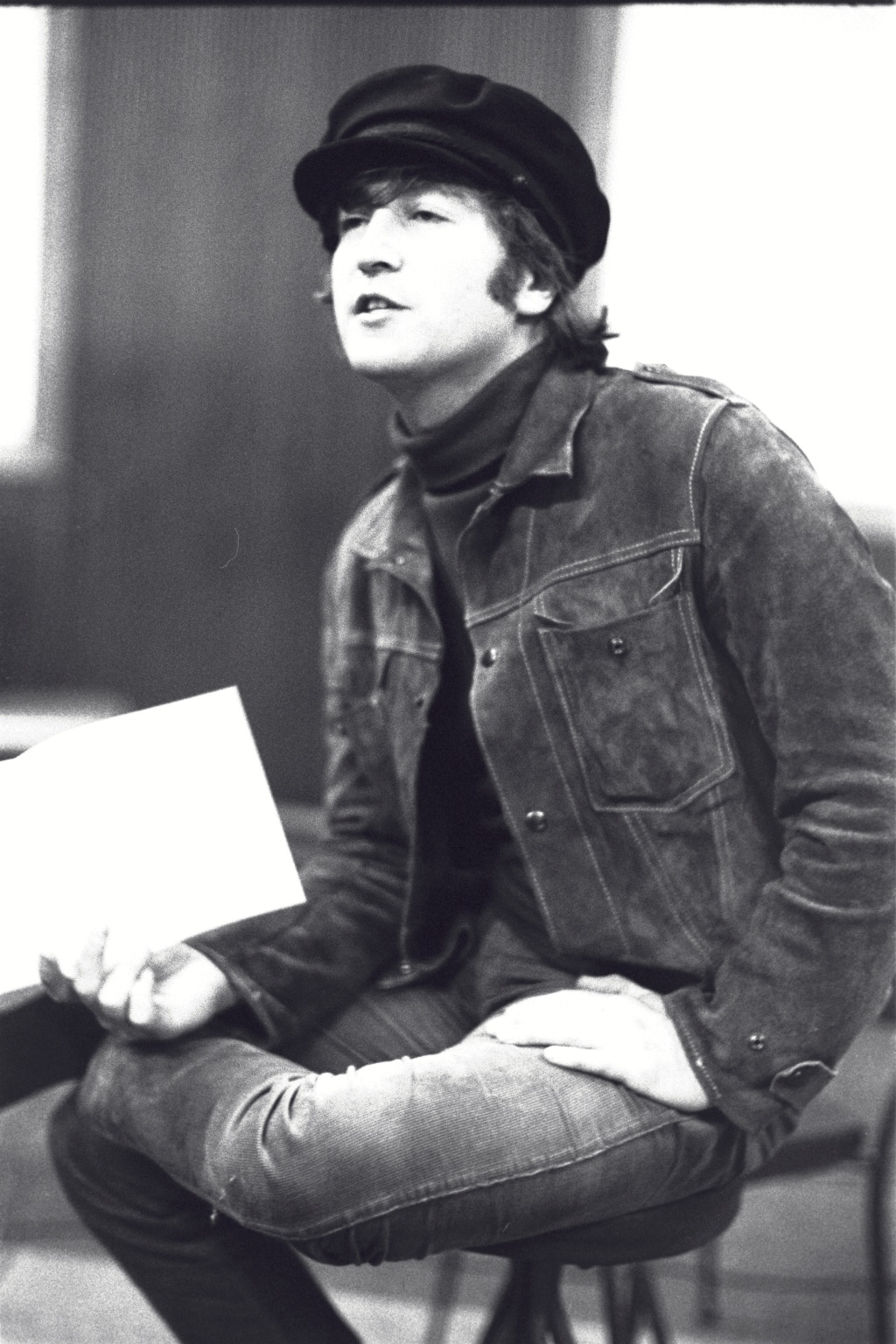

Jude Southerland Kessler: Erin, the recording of “And Your Bird Can Sing” took two long days of studio work – 13 takes! Yet, in The Beatles Anthology, John Lennon categorizes “And Your Bird Can Sing” as “one of my throwaways.” This is a typical Lennon “tell,” a phrase he consistently uses to characterize songs that reveal too much emotion, leaving him vulnerable. John applies the epithet to 1965’s “It’s Only Love,” which explores the deepening rift in his relationship with Cynthia. He applies it to “Run for Your Life,” a song that lays bare his jealously and feelings of inadequacy. (He told David Sheff that only after his Primal Scream therapy was he able to write a song openly about these feelings: “Jealous Guy.”) Is it possible that John is rebuffing other deep-seated emotions in this song as well?

Erin Torkleson Weber: A “throwaway” song would presumably come across as (by Beatles standards, anyway) formulaic and relatively unremarkable, and “And Your Bird Can Sing” is neither. John’s ex post facto dismissal of its significance (he criticized it several times after the band’s breakup, both in 1971 and 1980) doesn’t erode the song’s lyrical bite and sharp edges, which appear to offer a glimpse into John wanting, for lack of a better term, “top billing” from someone with whom he’s connected, and whose preoccupation with tangential things is apparently mucking up their connection with and understanding of the singer, John. Given what we know of John’s deep-seated, lifelong fear of abandonment, this reading of the song would make it the furthest thing from a throwaway; rather, it can be seen as an expression of insecurity and frustration at an important someone’s not prioritizing him and letting him down by not “getting” him. One of the authors to underscore this song’s possible emotional significance is Tim Riley, who notes “the implied rejection” (Riley, Tell Me Why, 192) evidenced by the snag in Lennon’s vocalization of “me.”

However, Riley appears to be one of the authorial exceptions. In his excellent work, Can’t Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain and America, Jonathan Gould describes “And Your Bird Can Sing” as “directed at an anonymous adversary,” (Gould, 359), and that adversarial component is what has drawn the most focus and encouraged significant speculation over the decades, by numerous authors, over whom John is addressing. Theories have ranged from Mick Jagger to Frank Sinatra, usually arguing that the song was provoked by Lennon’s “professional jealousy” (Gould, 360) and/or his dismissal of individuals whose pretension blinded them to true enlightenment. (Turner, Beatles’ 66: The Revolutionary Year, 160).

Yet these interpretations tend to ignore that, at the same time it criticizes, “And Your Bird Can Sing” also attempts to offer its subject some reassurance. “I’ll be round,” is, after all, wrapped inside the warning “you don’t get me;” a very appropriate lyrical pivot for the emotionally mercurial Lennon. This appears to indicate that, once the subject has tired of their pretentious distractions, Lennon and the song’s subject can possibly “see” one another and connect.

This reading of the song would certainly seem to eliminate Gould’s speculation that it was directed at Sinatra, to whom John would hardly be inclined to want to “see” or “get” him. And Faithfull’s speculation that the song was directed at Jagger (identifying her, Marianne, as the “bird” in the song) is purely that, speculation. (Rodriguez, Revolver: How the Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, 89). This overall reading of the song inevitably leads us to the question: Whom did Lennon feel, during this point in the Revolver sessions, wasn’t understanding him or prioritizing him the way he needed? That’s a level of lyrical analysis that’s above my historian’s paygrade, but a fascinating question to ask, particularly given John’s latter strong dismissal of the song.

Kessler: Erin, as a follow-up question… In the wake of his successful volumes, In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works, John had contracted with Jonathan Cape Publishers to write a third book to be released in February 1966. And writing was important to John. Indeed, when asked by Kenneth Allsop which profession he would prefer if he could choose between writing songs or writing books, John immediately chose writing books. He told Allsop he’d been doing that long before he became a Beatle. However, by the end of 1965, John admitted that he had only one poem prepared for the upcoming book, and so, he abandoned the idea of publishing again. Of course, John’s unrelenting schedule in 1965 must have had a great deal to do with that decision. But, do you think it’s possible that songs such as “And Your Bird Can Sing” gradually supplanted John’s need to write emotional, soul-revealing poetry and prose?

Weber: This is an excellent question, because it offers a chance to delve into issues regarding John’s creative process, and how that process was impacted by external and internal factors. What’s interesting about John’s schedule in 1965 is that you can make the argument his earlier schedules from the years when he wrote In His Own Write, published in 1964, and A Spaniard in the Works, which was published in June of 1965, were equally frantic. Why would this demanding schedule only begin to slow down his literary productivity by the end of 1965, when it hadn’t seriously impacted it before? Having said that, you can certainly argue that it was the cumulative effect of what had been, at that point, approximately three years of an unrelenting schedule, frantic pace, and constant demands of new songwriting material that played a role in preventing John from producing his third book.

We can speculate on any number of reasons, in addition to his frantic schedule, as to why John ultimately didn’t produce his third book. John told Allsop that he preferred writing books to writing songs, but the reality is that contractual and studio demands unquestioningly and unrelentingly prioritized song writing. So did the band’s group ethos and his competitive partnership with Paul.

Additionally, the argument that John’s realization that he could use song lyrics, such as those in “And Your Bird Can Sing,” to express the emotions previously and primarily expressed in his poems, letters and cartoons is a convincing one. In The Art and Music of John Lennon, John Robertson notes how Lennon’s “prose and verse writing had once been a form of exorcism,” (Robertson, 50) but argues that the lyrical example of Bob Dylan, coupled with the sonic possibilities in the studio, essentially allowed John to exorcise these elements through songwriting in a way that he had never previously considered or been able to accomplish.

Finally, we have to note that this use of self-revealing lyrics, replacing the old outlets of poetry and prose, corresponded with John’s initial exposure to and use of LSD. Robertson discusses how Lennon’s LSD use seriously influenced his writing and also argues that, in contrast to “the more fixed medium of prose,” songwriting allowed Lennon to express “these vague, shifting feelings” created by the aforementioned LSD use. (Robertson, 50)

Kessler: To conclude, what’s your reaction to this song, Erin? Does it speak to you in any way? Musically? Lyrically? Emotionally?

Weber: For me, “And Your bird Can Sing” is an excellent case study of how our connections and reactions to songs can shift with time and experience. As a bookish, four-eyed, awkward pre-teen with only a few (but amazing, essential, now lifelong) friends, every time I heard “And Your Bird Can Sing” on my dad’s Beatles tapes, I heard it as an indictment of the “cool” crowd in my middle school: fellow preteens so obsessed with wearing the right pair of brand-name sneakers that anyone, no matter how smart or funny or warm or generous, who didn’t meet their superficial standards was shunned or teased: “You say you’ve seen the seven wonders…but you don’t see me.” It went both ways, too: in my mind, if you were the sort of individual who cared so much about such trivial, adolescent status symbols that you couldn’t bother to look beneath the surface in order to know the person underneath, I didn’t want to waste my time attempting to get to know you, either.

Decades later, and (thankfully) well removed from middle school, I have a deep appreciation for the song’s lack of sentimentality. “And Your Bird Can Sing” is a song about attempting, and failing, to connect with someone. This is a feeling to which almost everyone can relate. Yet there’s no self-pity in it, and no sentimentality. I’m not a musician, or a musicologist, but my interpretation is that every other musical aspect of the song – the strident guitars, the edge in John’s voice – serves the song well. Its blend of warning over how prioritizing the wrong things – “prized possessions” – has damaged a point of connection between two people, combined with the singer’s frustration at feeling unseen and unheard, makes it relatable. Connections between people can and do fray, and while they can be patched, this song lays bare how it feels when that distance starts to occur.

What’s Changed:

Generally, this segment of the Fest blog precedes the “Fresh, New Look” interview. However, Erin Weber’s responses were so integral to the information in the following section that for this month, we’ve shifted things around. The aspect of “And Your Bird Can Sing” that has changed most over the years is the presumed identity of the protagonist, the “you” in this song. There have been many theories and suggestions proffered. Based on 37 years of study of John’s life and personality, I’m postulating yet another theory. Fifty-nine years after the song’s composition, however, no one can conclusively prove John’s intent. – Jude

As historian Erin Torkleson Weber so adeptly pointed out, Beatles experts and biographers have, over the years, offered myriad suggestions about the identity of the person to whom this song addressed. Others have claimed that they were the subjects of the song, although they can’t explain why Lennon was so annoyed with them. Marianne Faithfull, for example – as Erin indicates – swore the song was about her, claiming John’s jealousy toward Mick Jagger and herself. But Faithfull’s claim falls flat when we discover that 1) John genuinely liked Mick Jagger and 2) John wrote this song before Marianne and Mick were even “an item.”

Cynthia Lennon, who once gave John the gift of a wind-up songbird, thought the song was directed at her and said so in her first book, A Twist of Lennon (p. 128). But when we closely examine the lyrics, Cynthia meets none of the criteria to be the song’s protagonist. Cynthia had only traveled a limited number of times and all of those excursions were taken with her husband: to Ireland, Paris, Tahiti, and America for The Beatles’ Feb. 1964 visit. (Her visit to India was yet to transpire.) Cynthia had never visited exotic locations or seen “Seven Wonders.” Additionally, she knew very little about sound and music, and most crucially, she certainly didn’t have everything she wanted. John’s lyrics simply don’t fit Cynthia’s profile.

Lately, a YouTube video from James Hargreaves (which is well-presented) offers up Frank Sinatra as the song’s possible protagonist because Sinatra edged out The Beatles for The Grammy’s “Album of the Year” award in 1965 with the LP, September of My Life – and because Sinatra intensely disliked The Beatles and said so.

However, John and Paul had never “given a whit” for gold records, titles, or honors. By the summer of 1965, John had quit attending the Ivor Novello Awards. All of The Beatles complained about appearing at innumerable gold record ceremonies. In fact, in August of 1965, when compelled to attend the celebratory cocktail party given for them by Capitol Records president, Alan Livingston, George flatly refused to attend; Paul left early, and John departed not long after Paul. Such laudatory proceedings had become tedious.

All The Beatles really wanted to do was make great music. And as they returned to EMI in October of 1965 to create what would become Rubber Soul, they were inspired (and not threatened) by American competitors such as The Lovin’ Spoonful and the Byrds. In fact, the more talented their competitors (The Stones, the Byrds, the Beach Boys), the more The Beatles respected and liked them!

Frank Sinatra hardly registered on The Beatles’ radar. If the performer didn’t appreciate their hair or their style or even their personalities…well, who cared? Yet the tone of “And Your Bird Can Sing” is anything but milquetoast. It is angry. Very angry. John Lennon is singing to someone who really matters to him. Indeed, it appears that John is speaking directly to someone he knows – someone close to him whom he feels has betrayed his trust. We know this is the case because, as Erin pointed out, John vows in the bridge that no matter how cruel the person is to him,

“Look in my direction,

I’ll be ’round; I’ll be ’round.”

In other words, John has no intention of turning his back on the offender. Despite perceived disloyalty demonstrated by his former friend, John promises that he will always be there.

So, who is the protagonist of this song? John supplies numerous (though cryptic) clues to the betrayer’s identity:

- The person has “everything he wants.” (The protagonist is well-to-do: living in a chic locale and driving a prized car, making headlines and rubbing shoulders with the rich and famous, succeeding in a powerful career.)

- The person has “seen Seven Wonders.” ( In other words, the individual is well-traveled: having seen the world from the Spanish Riviera to the width and breadth of North America to exotic Hong Kong, New Zealand, and Australia. In John’s eyes, this person has seen it all, done it all. The protagonist is far more cosmopolitan than John, more polished and experienced.)

- The person purports to “have heard every sound there is.” (This tidbit clues us into the fact that the individual in question is, quite possibly, part of the music industry. However, John’s legendary sarcasm here hangs on two words: “you say.” John is smirking as he hisses, “You say you’re a music expert. You say you’ve heard every sound there is.” We get the feeling that the individual to whom John is singing has made unwelcome suggestions to John about his own compositions or performances.)

- The person has quirky, idiomatic tastes. (Well, after all, his bird is green…which leads us to perceive him as exotic and singular for his day.)

- Finally (and most significantly), this individual is extremely important to John. In fact, according to the lyrics, at an earlier point in their relationship, John wrongly assumed this person, “got him,” “understood him,” “heard him,” and “saw him.” Now, in the sunless backlash born of faithlessness, John is striking out with a lacerating verbal attack.

Who fits this five-point profile?

Who had a very intimate relationship with John – so deep that he shared John’s secrets and trusted John with his own? Who had been so close to John that it was rumored by mutual associates such as Yankel Feather and Joe Flannery that a possible love affair might exist between the two? Who had been John’s advocate before possessions, world travels, the myriad demands of business, and the intricate web of power struggles set in? If your answer is “Brian Epstein,” then we’re on the same page.

It is the reference to the “green bird” that really highlights Brian’s identity for us. In Liverpool’s Scouse lingo, a “baird” is a term for a girl or a girlfriend. And “to swing,” in the 1960s, meant “to step out from the norm sexually.” Thus, John’s reference to his friend’s unusual “green bird” – a bird who “swings” – was, in all likelihood, a bitter Lennonistic dig at Brian’s gay relationships. Indeed, on The Anthology version of this song, when Paul and John sing, “and your bird can swing,” they snicker naughtily at their sly double entendre.

If we agree that John is, in fact, addressing Brian in this song, a second question immediately arises: What would have caused John to become angry enough with Brian that he penned this attack – a song only slightly less hostile than “How Do You Sleep?”

By 1966, John ached to stop touring. All of The Beatles did. And although they had expressed that sentiment to Brian over and over again, he completely ignored them. While this was frustrating for Paul and George, it seemed a personal wound for John.

In December of 1961 – upon assuming management of The Beatles – Brian had pledged to Mimi Smith that no matter what happened to the other boys, he would always protect John. He had vowed to work tirelessly to defend her nephew’s best interests. But now, John feels that Brian has stopped putting him first. Consumed with what John has decided is a desire for wealth, fame, and power, Brian (John thinks) is pushing The Beatles too hard – callously demanding new films, tours, singles and LPs, interviews, radio shows, television programmes, and personal appearances. And once upon a time, Brian had promised better.

Hence, John lashes out with real invective, linking each verse with the string of repeating accusations. “You don’t hear me!” “You don’t see me!” “You don’t get me!” John sees Brian’s refusal to address his needs as a broken vow, an infidelity.

This song, therefore, fits snugly into the “broken relationships” theme of Revolver. Originally entitled, “You Don’t Get Me!” this song shatters the giddy mood of “Good Day Sunshine.” Track Two of Side One gave us “Eleanor Rigby.” Here comparably, in Track Two of Side Two, John and Brian are “the lonely people,” standing in a church of abandoned promises, surrounded by memories from May of 1963, when they vacationed together for 10 days on the Spanish Riviera or September 1963 when they spent happy days alone together in Paris. During those times, John and Brian had formed a bond born of shared vulnerabilities rarely voiced to anyone else. They had reached out to one another in mutual trust. Now, a mere three years later, John is spewing fury over the perceived perversion of that trust as Brian steadily continues to insist upon the course he feels The Beatles must follow.

For the wounded John Lennon, having “everything you want,” “seeing Seven Wonders,” “knowing every sound there is,” and even owning an exotic green, swinging bird means nothing if, in the process of garnering such success, you sacrifice friendship. Frustrated and fuming, but promising to “be ’round” when Brian finally hears him, sees him, and gets him once again, John is hanging on. However, the unresolved chord at the end of this song reminds us that in the future, anything can happen.

Sadly, by August of 1967, anything did happen. Fame exacted its price. And the birdsong fell silent.