Revolver

Side One, Track Six

“She Said She Said”

by Jude Southerland Kessler and Christine Feldman-Barrett

Through 2023, the Fest for Beatles Fans blog has been enjoying some time well spent with the songs on The Beatles brilliant LP, Revolver. This month, Christine Feldman-Barrett joins Jude Southerland Kessler, the author of The John Lennon Series, for a fresh, new look at one of the most beloved Beatles tracks of all time. Christine Feldman-Barrett is a youth culture historian and Beatles scholar.

Originally from the United States, she is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia. She is the author of A Women’s History of the Beatles, which was published with Bloomsbury in 2021 and was awarded the 2022 Open Publication Prize by the Australia-New Zealand branch of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music (IASPM). Her other publications include “We are the Mods”: A Transnational History of a Youth Subculture (Peter Lang, 2009) and – as editor – Lost Histories of Youth Culture (Peter Lang, 2015) and The Life, Death, and Afterlife of the Record Store: A Global History (Bloomsbury, 2023). Feldman-Barrett and her work have been featured in the Washington Post, the Guardian, the BBC, and ABC radio Australia. She has appeared as a guest on numerous Beatles podcasts and is on the editorial board of The Journal of Beatles Studies, which is published by Liverpool University Press. And best of all, Christine will be at the New York Fest for Beatles Fans, 9-11 February 2024! Come meet her in person!!!

What’s Standard:

Dates Recorded: 21 June 1966

Time Recorded: 7.00 p.m. – 3.45 a.m.

Studio: EMI Studios, Studio 2

Tech Team:

Producer: George Martin

Engineer: Geoff Emerick

Second Engineer: Phil McDonald

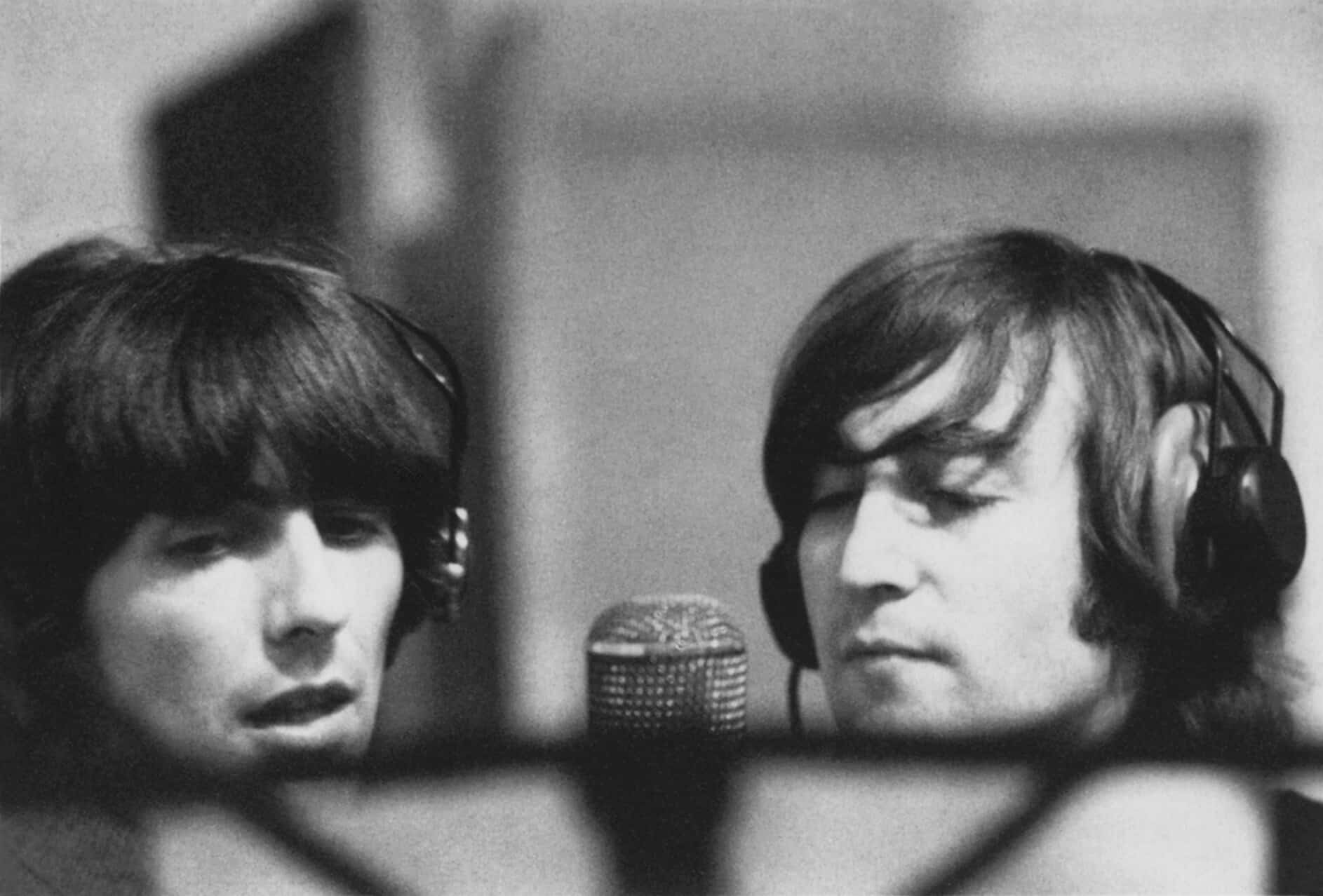

In Studio 2, The Beatles worked for 9 (number 9!) hours to record this final song for the Revolver LP. “She Said She Said” came into the session unnamed and unrehearsed. Through 25 takes, the boys assembled all the elements and honed the song. The rhythm track of Take 3 was deemed “best” and onto this, John superimposed his lead vocal…and John and George dubbed in their backing vocals. As Mark Lewisohn explains in The Beatles Recording Sessions, “A reduction mix vacated one of the four tracks where an additional guitar and organ part (played by John) were soon taped.” (p. 84) The role of Paul and the bass line heard on this song will be discussed in the “What’s Changed” segment of this blog.

Instrumentation and Musicians:*

John Lennon, the composer, is playing either his 1961 Fender Stratocaster or his 1965 Epiphone ES-230 TD, Casino.

Paul McCartney says he did not sing or play an instrument on this track. (See “What’s Changed”)But many sources still list him as providing the bass on his Rickenbacker 4001S before having an argument with one or more of The Beatles and walking out of the session.

George Harrison is playing either his 1961 Fender Stratocaster with synchronized tremolo, his 1964 Gibson SG Standard with Gibson Maestro Vibrato, or his 1965 Epiphone ES-230TD, Casino with Selmer Bigsby B7 vibrato.

Ringo Starr is playing his 1964 Ludwig Oyster Black Pearl “Super Classic” drum set.

*This information is from Hammack’s The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, 154.

Sources: Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, 226, Lewisohn, The Beatles: The Recording Sessions, 84, The Beatles, The Anthology, 209, Margotin and Guesdon, All the Songs, 336-337, Winn, That Magic Feeling, 27-28, Womack, Long and Winding Roads, 142-143, Hammack, The Beatles Recording Reference Manual, Vol. 2, 154-156, Rodriguez, Revolver: How The Beatles Reimagined Rock’n’Roll, 149-151, Turner, A Hard Day’s Write, 111, Davies, The Beatles Lyrics, 164-165, Miles, Many Years From Now, 288, Spizer, The Beatles for Sale on Parlophone Records, 215, Spizer, The Beatles Rubber Soul to Revolver, 219, MacDonald, Revolution in the Head, 168-169, Mellers, Twilight of the Gods, 75-6, Spignesi and Lewis, 100 Best Beatles Songs,186-188, Spitz, 581, and Riley, Tell Me Why, 188-189.

What’s Changed:

- Experimentation with Meter – A month ago, if someone had asked me which Beatle most experimented with meter and tempo changes, I would have swiftly responded, “Oh, Paul McCartney.” But as it turns out, that is not true. Here are the songs in which John Lennon experimented with meter change: “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite,” (4/4 in the verses, 3/4 waltz in the instrumental bridge), “All You Need is Love,” (intricately alternates between 4/4 and 3/4), and “Across the Universe” (Verse One is 4/4 until it reaches the last bit of the verse, “across the universe,” and that is 5/4. Verse Four repeats almost the same thing but this time the words “way across the universe” are in 5/4.) Of course, John also employed myriad meter changes in “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” and “Happiness is a Warm Gun” (2/4, 3/4, and 4/4!!!)

Two of the earliest Lennon/McCartney songs to dabble in meter change were “We Can Work it Out” (recorded during 20 October 1965) and “She Said She Said” from June of 1966. As Ian MacDonald points out in Revolution in the Head, “She Said She Said” is “rhythmically one of the most irregular things Lennon ever wrote.” (p. 169) It not only features a signature change into 3/4 during the “She said, ‘You don’t understand what I said.’ I said, ‘No, no, no, you’re wrong,’” portion of the song. The disjointed, otherworldly sensation of a hazy dream state or an LSD fog – accentuated by the eerie consideration of “what it’s like to be dead” – manifests in an erratic, herky-jerky zombie-esque arrangement. Dreamlike – nightmarish, really – the strange tempo pushes and pulls, threatening to obliterate sanity. It’s a powerful tool placed alongside the unusual instrumentation and The Beatles’ vocal elements.

- Possible Limited McCartney Input – Although “She Said She Said” was the closing track for Side One of Revolver, it was actually the final song recorded for the LP. The Beatles had begun work on Revolver on Wednesday, 6 April 1966, (Lewisohn, The Beatles: The Recording Sessions, 70) and they’d been working quite closely together, hours on end for almost four months. So, it’s no surprise that on this final evening, tensions were running high. Paul recalls, “I think we’d had a barney or something, and I said, ‘Oh, fuck you!’ and they said, ‘Well, we’ll do it.’ I think George played bass.” (Margotin and Guesdon, 337) Note: In The Beatles Lyrics, Hunter Davies qualifies this by saying, “…Paul does not appear on that track, not as a singer anyway, though he might have added a bit of bass afterwards.” (p. 164)

However, John C. Winn in That Magic Feeling states, “Paul became the first Beatle to walk out on a session when he had an unspecified argument with the others, although not before contributing to the rhythm track.” Hammack in The Beatles Recording Reference Manual agrees, saying that on the 21st of June, “Take 3 was best, and a good thing, too, because afterwards, McCartney got in a fight with Lennon and left the studio.” (p. 154) But in Many Years From Now, Paul firmly states that he did not perform on the track: “I think it was one of the only Beatles records I never played on.” (Miles, 288) Did he, or didn’t he? This shall remain one of the great mysteries of Beatles history.

- Lyrics by Lennon and Harrison – On 21 June 1966, in an interview with Melody Maker (which would appear in the magazine on the 25th) John revealed that he still had one song to record for the new LP, but that he had only written “about three lines so far.” George Harrison recalls trekking over to Kenwood during that time frame to help John “wrap up the composition.” George recalls that he suggested John incorporate a waltz-tempo fragment of a song (“When I was a boy, everything was ri-ight/Everything was ri-ight…”) that John had formerly created and had left unused. George says they worked together to link this song fragment to the rest of “She Said She Said.” (Winn, That Magic Feeling, 27)

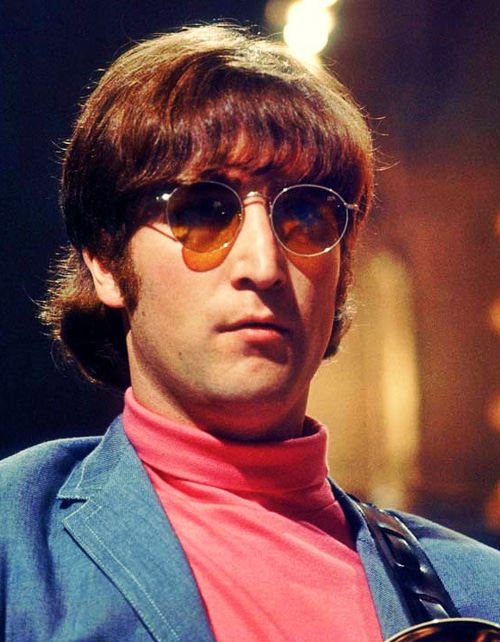

- A “Story” Version of Lennon’s Lifelong Theme – John insisted that while Paul wrote “songs about other things,” John mainly wrote about himself. And in “She Said She Said,” John is still focusing on his autobiographical pain: the devastation that death leaves in its wake, the chaos of sorrow and loss. However, in “She Said She Said,” John shares this torment via the story of a woman whom he supposedly encounters…a strange female who tells him that she “knows what it’s like to be dead,” that she “knows what it is to be sad” – a woman who makes him feel as if he’s “never been born.” In Twilight of the Gods, Mellers admits that this appears to be an older woman, perhaps “an aunt or mother.”

Indeed, although the line, “I know what it is to be dead” was inspired by a comment from Peter Fonda at a 1965 Los Angeles pool party, Fonda has nothing to do with the subject of this song. John is once again singing his heart, bemoaning the devastating loss of Julia Lennon, “the girl in a million my friend.” But here – for the first time – he is doing so in a narrative format. In this story-song, the familiar woman who rules his entire musical catalog appears as surreal: as a ghost, a spirit, or a figment of his imagination.

This is unique territory for John, who up to this point has stuck very closely and literally to the poignant narrative of Julia’s loss twice in his life: first, when he was separated from her in childhood and later, when as a teenager he lost her a second time, to death. In “Help!,” “I’ll Cry Instead,” “Not A Second Time,” “(You’ve Got To) Hide Your Love Away,” “Nowhere Man,” “I’m A Loser,” “Julia,” and so many more, John consistently poured out his heartbreaking tale without imaginative embellishment. But here, the old story – no less painful in an artful form – is entangled in the bizarre trappings of a dream state. The same fears, pain, and anguish are merely housed in a unique presentation.

A Fresh New Look:

It was a joy to work “across the universe” (she, in Australia and I, in Louisiana) with Dr. Christine Feldman-Barrett to trace the musical and storyline innovations inherent in Lennon’s brilliant “She Said She Said.” Christine will be at the February 9-11, 2024 New York Fest for Beatles Fans to share her respected work on A Women’s History of The Beatles. We welcome Christine to the Fest Blog and can’t wait to hear her speak in just a few months!

Jude Southerland Kessler: “She Said She Said” has been called one of John’s most revealing biographical songs. Tim Riley in Tell Me Why states, “the singer is wrestling with feelings he barely understands – inadequacy, helplessness and a profound fear. Because Lennon so obviously feels these emotions as he plays and sings them, the music is a direct connection to his psyche.” (p. 188) What is your reaction to this assessment?

Christine Feldman-Barrett: Unless someone had insider information at the time, no one in The Beatles’ audience circa 1966 would have known that the song was about one of John’s first LSD experiences – nor that that some of its lyrical content was about a ‘he,’ namely, actor Peter Fonda. Instead, what comes through in the lyrics is very much a sense of emotional confusion. That feeling is certainly key to the words of “She Said She Said.” However, there’s also an element of intellectual detachment to the narrator’s telling of this story. Unlike 1965’s “Help!,” which is lyrically direct in showcasing Lennon’s vulnerability, “She Said She Said” is very much head over heart. Needless to say, a “heady” reading of the song makes perfect sense once listeners know it’s about John Lennon taking a hallucinogenic drug.

The track’s psychedelic origin story aside, what’s especially interesting upon first listen is that it seems the narrator is having a deep and meaningful – if also somewhat esoteric – conversation with a woman. I don’t think I had ever encountered that kind of male-female dialogue in a song before I listened to “She Said She Said.” And though the “he said” parts of the lyrics are seemingly critical of what the woman is saying, the man in the song is nonetheless hooked into this conversation for a while (until, that is, “he’s ready to leave”). As Jacqueline Warwick states in her 2002 book chapter, “I’m Eleanor Rigby: Female Identity and Revolver,” the song seems to be about “a woman who will not stop talking and a man who doesn’t want to listen (but has difficulty tearing himself away).” (p. 61)The fact that something “she” says makes the song’s male protagonist want to question his existence was something completely different to my young ears in 1979, and it is definitely something that would have been atypical for a rock song in 1966.

Even when I was a child listening to this track, I liked the idea that the woman in the song – and her purpose within the lyrical story – is unusual, mysterious. She does not come across as a love interest, as would hold true for other, earlier Beatles songs or songs by other artists circa 1965 or 1966. Instead, this woman is an enigmatic character who wants to discuss life and death with her conversation partner – even if it upsets him – and even if it makes him question his entire sense of self and the world as he knows it.

Along these lines – with a conflict between man and woman in the lyrics – I also think about how Cynthia Lennon’s 2005 memoir John addresses how her husband’s LSD use affected their marriage. Cynthia had no interest in the drug and found it frightening while John found it profoundly life changing and affirming – maybe because it brought him out of his “known self” or challenged his sense of himself as a Beatle. In Cynthia’s estimation, however, LSD drove a wedge through their marriage (see, for example, her thoughts on this in Chapter 13 of John). If John’s perspective of himself and the world was forever altered, it created a new type of relational space in which Cynthia likely felt she no longer truly belonged.

Kessler: Christine, the closing song on Side One of a Beatles LP was traditionally something rather remarkable. On Please Please Me, it was the title track, “Please Please Me.” On A Hard Day’s Night, it was the Ivor Novello award-winning, “Can’t Buy Me Love.” On Help!, the closer was “Ticket to Ride.” What elements of “She Said She Said,” in your opinion, recommend it into this pivotal position on Revolver?

Feldman-Barrett: That’s a great question. It makes me think about how the other closing track on Revolver, “Tomorrow Never Knows,” is the one that often vies for the spot of “Best Beatles Song” (alongside “A Day in the Life”) in most rankings and lists I’ve come across. But for my money, “She Said She Said” should be near the top as well. One of the reasons it’s remarkable is because The Beatles – John first and foremost – are trying to sonically achieve something really very difficult with this song: relaying the experiences of an acid trip.

While we take the notion of “psychedelic rock” for granted today, the idea of replicating such a singular experience in musical form could not have felt straightforward or easy. While Lennon was able to describe to George Martin the sound and feel he wanted for “Tomorrow Never Knows” (i.e., monks chanting from atop a mountain) – and he had Paul’s tape loops to assist – how would it be possible for just guitars, drums, and vocals to aurally mirror LSD’s effects? Though I have never taken LSD myself, reading anecdotes about acid trips and having had others share their experiences of them with me, it’s clear that this song is trying to create a sonic representation of something that is often described as comprising many visual sensations and hallucinations. For example, in The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver through Anthology (1999), Walter Everett theorizes that the lead guitar’s echoing of the vocal melody throughout the song is a motif meant to intimate the visual trails that are said to occur while taking LSD. (p. 66) Moreover, the unusual and changing rhythms of the song – clearly led by Ringo’s drumming – seem to capture the oddity of time itself while tripping.

While all music deals with and works within time signatures, trying to get the feeling of psychedelic time distortion just right – and without the whole song falling apart – is such an interesting thing for The Beatles to have attempted here. And the fact that it’s mostly achieved through just their playing and singing – without any overt studio tricks like with “Tomorrow Never Knows” – is phenomenal. For all these reasons, “She Said She Said” definitely deserves this pivotal position on the Revolver LP.

Kessler: Christine, this was the final song recorded for Revolver, and Ian MacDonald says “Lennon pull[ed] off a last-minute coup with this track, going some way towards evening up the score in his on-going competition with McCartney.” (Revolution in the Head, 169) Although Paul has more songs to his credit on the LP than John does, MacDonald says, “‘She Said She Said’ is the outstanding track on Revolver.” (p. 169) Your reaction?

Feldman-Barrett: I absolutely agree with Ian MacDonald’s reading of “She Said She Said,” and I am always surprised when I hear Beatles aficionados dismiss it as a kind of throwaway track. I know that for some, this has to do with the claim that Paul didn’t play bass on it (though the claim is disputed). In any case, that dismissive view of this song is difficult for me to understand. Then again, I am a particular fan of The Beatles’ late ’65 to early ’67 sound, and – to me – this song typifies everything I love about that period of their music-making.

It’s clear that McCartney’s songs on Revolver are magnificent examples of his artistry in so many ways – and that he was really growing as a songwriter with this album – but when I think of Revolver – I tend to think of John’s songs first, with “She Said She Said” and “Tomorrow Never Knows” the two that immediately spring to mind. They are both oddly thought-provoking and memorable. While Paul’s songs on Revolver are filled with pathos and are finely crafted “story songs,” I find the otherworldly aural beauty of Lennon’s contributions more intriguing listen after listen. And of all the “John songs” on Revolver, “She Said She Said” is the ultimate earworm. Its melody is nothing short of addictive. Little wonder that MacDonald also suggests Lennon is at his creative peak with The Beatles during this time. His songs on Revolver – though fewer in number than those led by McCartney – are landmark moments in rock music history due to their sheer inventiveness.

Kessler: Christine, when this song debuted, I was a pre-teen living in small-town North Louisiana, and I remember being utterly bewildered by the track. Now, thanks in large part to Robert Rodriguez’s book Revolver: How The Beatles Re-Imagined Rock’n’Roll, I can appreciate the layered artistry of the work. But it still isn’t one of my favorite Beatles songs. How did you respond when you first encountered “She Said She Said,” and how do you see it now?

Feldman-Barrett: I was seven (almost eight) years old when I first heard this song in 1979, and I loved it straight away. As an adult looking back on this moment, my initially enthusiastic first reaction to “She Said She Said” kind of bewilders me on the one hand, as it doesn’t seem the kind of Beatles track a little girl listening to Revolver would necessarily enjoy. On the other hand, I’ve always been drawn to a jangly guitar sound, which is so prominent in this song. I know it’s been said that this was the Byrds’ influence on the song, but I don’t think I had heard the Byrds’ music yet by this time.

In any case, George’s lead guitar line, which opens the track, commanded my attention to such a degree that I could not help but be intrigued by the rest of the song. Also, while the song showcases a dramatic change in rhythm and meter, it’s nonetheless always been a Beatles song that makes me want to get up and dance. The lyrical content of “She Said She Said” was not something I thought much about until I was a teenager. Being part of the Goth subculture during those years – and a Goth who hadn’t abandoned The Beatles – I know the brooding, existentially angsty nature of the song’s lyrics was definitely appealing. Despite its attractiveness to me at that time, “She Said She Said” is a song that has traveled really well with me throughout my life. It always gels with or complements other music I enjoy.

Since my sister held onto the Revolver LP she bought for us in 1979, I ended up buying it on CD soon after watching The Beatles Anthology when it first aired on American TV in November 1995. I’d play “She Said She Said” on repeat in my car driving around Los Angeles, which is where I lived at the time. Since the song’s origin story took place in LA, I suppose that was fitting – but, mainly, it made sense that I wanted to hear it a lot, given that I was also listening to Britpop bands like Oasis and Blur. There’s such a clear A-to-B line from “She Said She Said” to the sound of those bands, most all of whom cite The Beatles as one of their greatest inspirations. And it still remains my favorite Beatles song. There’s something magical about The Beatles’ early psychedelic songs that make me return to them again and again. For me, “She Said She Said” has all the elements that make me love their mid-period sound best: catchy guitar lines, inventive drumming, and vocal melodies that always makes me want to sing along.

For more information on Christine Feldman-Barrett, HEAD HERE or HEAD HERE

Follow Christine on X (formerly Twitter) HERE

Follow Christine on LinkedIn HERE

For more information on Jude Southerland Kessler and The John Lennon Series, HEAD HERE